Fla. pastor tackles problem of ‘Cultural Christianity,’ says unsaved Christians are prevalent

Calls it an ‘evangelism issue,’ not a ‘discipleship issue’

A Florida pastor is tackling what he considers to be the largest mission field in the United States: people who claim to be Christian but do not actually believe the Gospel.

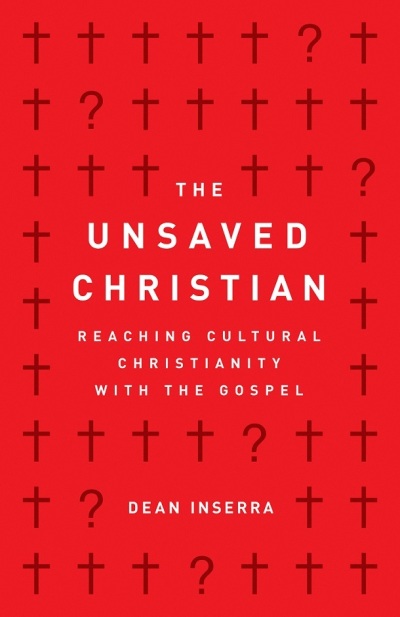

Dean Inserra, pastor at City Church Tallahassee and author of the recently released book The Unsaved Christian: Reaching Cultural Christianity with the Gospel, said it can be “complicated to figure out” who is a Cultural Christian, as such people will publicly identify as Christian even though “their answer for doing so would have nothing to do with the Gospel.”

"We wrongly think that it is a discipleship issue but I hope they can understand that it is a different religion altogether,” explained Inserra, who hoped readers of his book “gain a true understanding of how to reach what I believe is the most common mission field around them."

The Christian Post interviewed Inserra on Friday to discuss the prevalence of Cultural Christianity, church discipline, and his opinion of when to leave a mainline congregation. Below are excerpts from that conversation:

CP: Do you believe that the problem of Cultural Christianity is a recent development in the United States, or has it always existed in some capacity?

Inserra: I believe it has always existed in some capacity. I just believe that it is more prevalent today because indifference towards the things of faith while still maintaining to possess faith is very rampant.

CP: You discussed different types of Cultural Christians in the book. For example, “God & Country Christians” and “Generational Catholics.” Which of these sub-categories of Cultural Christianity would you say are the most common in the United States today?

Inserra: I would say two different ones. I would say the nominal Catholics are everywhere. A lot of times we think Cultural Christianity is confined to the Bible Belt, but the reality of nominal Catholics [shows] that is not true.

The other common one is what I could call “the guy next door.” The person that just really believes that they're a good person. They have a basic generic vague theistic belief. They're not atheists or agnostics and they really believe themselves to be good people.

Those people are hard to reach because they don't always see a need for the Jesus that they claim to believe in."

CP: Dietrich Bonhoeffer famously wrote about "cheap grace." Do you see parallels between the "cheap grace" Bonhoeffer described in The Cost of Discipleship and the Cultural Christianity you have written about?

Inserra: I do somewhat. More than it being about “cheap grace,” I think that you have to understand that Cultural Christianity is a different religion, altogether. I think some people believe that it is a discipleship issue; I think it’s really an evangelism issue.

But I think that the “cheap grace” idea has helped fuel Cultural Christianity wherein people think that they're Christians because they prayed a prayer when they were five or they were involved in church activities.

CP: In chapter 6, you wrote "we are not on a witch-hunt for falsely assured believers and should never disparage someone struggling to follow Christ and failing." How would you advise Christians to avoid the danger of turning a talk about faith with a Cultural Christian into a witch-hunt?

Inserra: I think we need to make sure that we are not declaring a struggling believer to be a Cultural Christian. They just might be growing or they might just need some repentance in their life.

Cultural Christians are simply people who do not believe the Gospel. They're generic theists — their answer to why they are a Christian is that they're basically not Muslim, Jewish, or agnostic or atheist. What makes it so hard to decipher is that there is no category for "Cultural Christian." If you filled any kind of paperwork that asked you to indicate your religion, there's no box that says “Cultural Christian.”

CP: Has there ever been a time when you have suspected a friend or member of your church to be a Cultural Christian only to find out in further conversation that they are in fact sincere believers in Christ?

Inserra: Yes, sure. And what has led to that realization is their ability to actually articulate the Gospel and define their faith by Jesus Christ. Maybe they just needed to grow. A Cultural Christian does not define their faith by Jesus Christ. So what has happened in those conversations is quickly I realize “OK, these people actually do understand the Gospel. They just need some help in discipleship.”

We need to make sure that we clearly understand the difference between someone who just simply has generic theistic beliefs and personal morality versus someone who actually is a Christian who maybe just is struggling.

CP: In the book, you discussed the need to have church membership mean something. What is your opinion of the practice of church discipline and does your congregation practice it?

Inserra: We do practice church discipline. We have actually never have had it get to the point where it came before the church. It’s always been handled by our elders. Thankfully, never gotten beyond that. But I think that really it’s a loving thing to do, to try to restore someone to a right relationship with the Lord, restore someone to church fellowship. I think churches that have no concept of that really just aren't taking sin seriously and are not taking their witness in the community seriously.

CP: In chapter 13, you discussed Cultural Christianity in the Mainline Protestant churches. The impression I got from reading the chapter was that you supported leaving congregations where theological liberalism is strong. The United Methodist Church, as you may know, is currently dealing with a lot of tension between its liberal and conservative wings. Do you believe that it would be best for the UMC to schism?

Inserra: If the Methodist church could actually be preserved for core biblical orthodoxy, then I think it would be worth staying.

If it wasn't for the African churches, it probably would have swung the way of denying biblical orthodoxy. I don't want my sentimentality and my heritage and my affection for something to override the truth of something. And I think that's what happens sometimes.

I personally left the Methodist church just because of the theological liberalism that was very present there.