Are Religion and Science at Odds? New Poll Says Maybe Not

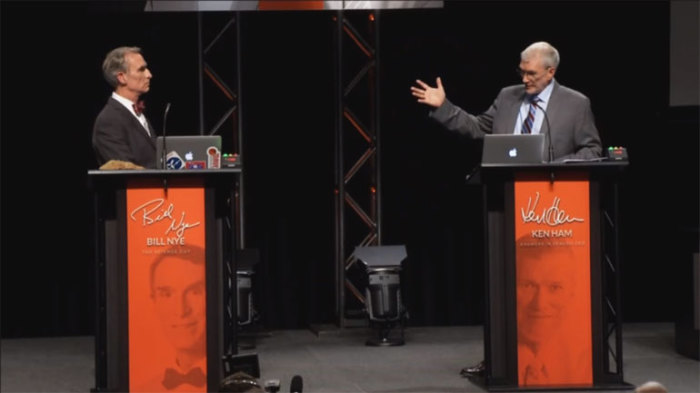

Despite what conclusions many Americans have arrived at following Ken Ham and Bill Nye's creation and evolution debate earlier this month, a new survey suggests that science and religion might not be nearly as antithetical as suggested by popular culture.

According to Rice University sociologist Elaine Howard Ecklund, who presented her findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science on Sunday, Evangelical Protestants were far more likely than the general public to believe that science and religion could work together.

"We found that nearly 50 percent of Evangelicals believe that science and religion can work together and support one another," Ecklund, the Autrey professor of sociology and director of Rice's religion and public life program, said in a statement. "That's in contrast to the fact that only 38 percent of Americans feel that science and religion can work in collaboration."

Results revealed that Evangelicals make up 17.1 percent of all scientists, while Christian's overall (including Mainline Protestants and Roman Catholics), make up 61 percent of the field. Thirty-six percent of scientists professed no doubt about God's existence.

The poll also suggests that the difference between the religious practices of scientists against those of the general population were not substantially divergent. Researchers asked 10,000 individuals about their house of worship attendance, religious self-identification, engagement with religious texts and prayer.

According to her findings, 20 percent of the general public affirmed that they attend weekly religious services; in only a two point spread, 18 percent of scientists also agreed with that statement.

Seventeen percent of the general public said they read a religious text weekly and 19 percent said they consider themselves religious; 13.5 percent of scientists, on the other hand, were likely to dive into the Bible, Torah or Quran weekly and 15 percent said they would call themselves religious.

The largest divergence regarding religious practice pertained to prayer. More than a quarter of the general population said they prayed several times a day, while 7 percent fewer, 19 percent of scientists admitted to communing with God that often.

Ecklund blames the media for creating a misperception that science and religion don't get along. Her research indicates that nearly 20 percent of the general population believe that religious people are "hostile to science," and just over 20 percent of the same group believe "scientists are hostile to religion."

"Most of what you see in the news are stories about these two groups at odds over the controversial issues, like teaching creationism in the schools. And the pundits and news panelists are likely the most strident representatives for each group," she said. "It might not be as riveting for television, but consider how often you see a news story about these groups doing things for their common good. There is enormous stereotyping about this issue and not very good information."

David Foster, a professor of biology and environmental science at Messiah College, agrees that the media have largely been responsible for promulgating division between religion and science.

"The media likes conflict. Conflict is a story, right?" Foster told The Christian Post. "In some ways there's a good reason to promote that conflict from both sides of the issue. Science without God and Christianity without science. There's a great fundraiser to be had when you can polemicize people and say, 'Well, we've got the answer on this side and they don't.' It makes good politics, but not necessarily good policy and a good way to proceed with things."

Foster also believes the majority people aren't "that polemic."

"Most people have some way of resolving conflicts, which is a more difficult route, or by compartmentalizing the conflicts sometimes and saying, 'Well, this is the religious life and this is my scientific life and they don't overlap.' I think that's rather uncommon. People who tend to pursue science tend to want answers," he said.