Can a Conscientious Christian Vote for Donald Trump?

From the start of the primaries through the Republican convention, I argued passionately in social media against Donald Trump. After the convention I kept hoping some strong conservative would run as a third-party candidate, splitting the Electoral College vote so much as to prevent anyone from winning there, and so turning the choice of president over to the House of Representatives.

My argument incorporated Trump's serious moral failings (with pride at the top) with his apparently complete lack of serious political philosophy, Constitutional understanding or commitment, and knowledge of policy domestic and foreign.

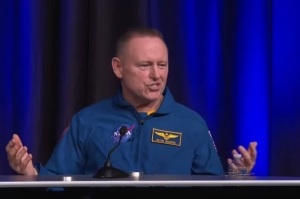

In a recent event at the National Press Club carried by C-SPAN, evangelical public leaders argued opposite sides about Trump.

Radio talk show host Janet Parshall and High Impact Leadership Coalition leader Bishop Harry Jackson, who pastors a church just outside D.C., both supported him. Radio talk show host and The Resurgent founder Erick Erickson and Bill Wichterman, Senior Legislative Advisor at Covington & Burling, LLP, and a former advisor to President George W. Bush, both opposed him. None recommended voting for Hillary Clinton.

Disclosure: Parshall, Jackson, and Wichterman are all friends of mine. I've not met Erickson. I respect the work and judgment of all four. They're serious thinkers, people of integrity, maturity, and wisdom.

World published a balanced, if necessarily incomplete, report by Washington Bureau Chief J.D. Derrick. Here I respond to part of Erickson's argument because it seems so widespread among Christians: Trump's immorality means Christians can't support him without compromising our moral witness.

Derrick summed up Erickson's argument thus: "… the 1 Corinthians 5 admonition not to associate with sexually immoral persons who claim to be believers applies today to the church universal."

It's a serious consideration.

But it doesn't adequately reflect the text and its context. Paul there instructs a church, not a nation, to excommunicate ("deliver … to Satan") a member unrepentant in sin so scandalous that even pagans wouldn't tolerate it (verse 1).

Paul expressly says,

"I wrote to you … not to associate with sexually immoral people — not at all meaning the sexually immoral of this world, or the greedy and swindlers, or idolaters, since then you would need to go out of the world. But now I am writing to you not to associate with anyone who bears the name of brother if he is guilty of sexual immorality or greed, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or swindler — not even to eat with such a one." [1 Corinthians 5:9–11]

I understand "who bears the name of brother" not as denoting everyone who claims to be a Christian (which would include millions of nominal "Christians" who don't even attend, let alone have membership in, Biblically faithful churches) but those who have been received into membership in the church.

It would be possible to read "associate" (Greek synanamignumi) as having any contact or pursuing any common goals with someone, but that fails to deal adequately with Paul's explicit qualification. Should every Christian refuse to be a citizen of a nation, or an employee in a business, including any unrepentant professing Christians? Citizenship and employment are, after all, forms of association.

Church membership and spiritual fellowship are what's at stake — not association in extra-ecclesial activities.

Further, being willing to vote for a candidate doesn't equal "publicly supporting" or being "in the public square advocating for" him or her. Seeing it that way reflects a false and naïve messianism — faith that one particular individual will deliver us from our woes.

Instead, a vote for a candidate is always a vote not for an individual but for a package — the more so the higher the office.

When I push the stylus through my ballot on election day (and as of now I remain undecided other than being quite sure I cannot vote for Clinton), I'll be voting not for an individual in isolation but for a package: that individual plus a running mate, plus the campaign platform, plus the relationship the President will have with members of Congress, plus the platform of the candidate's party, plus the 3,000 plus political appointees to be named within a few weeks of inauguration, plus scores to hundreds of federal judicial appointments over the next four years including at least one and possibly four or five Supreme Court justices whose judgments will shape American law and culture for decades longer than a president's term.

Personnel is policy, as M. Stanton Evans put it in 1981 when Ronald Reagan faced the challenge of populating his administration with qualified personnel who hadn't been in either the Ford or the Carter administration.

Finally, Christian ethics is a two-step process involving both moral obligation, or duty, and prudence, or the choice of permissible means toward permissible ends.

Of every option, whether of ends or means, we must first ask, "Does God's revealed moral law prohibit this?" If so, we must reject it, no matter the circumstances. If not, it is morally permissible, and we can at least be sure that we don't sin by choosing it — for "sin is lawlessness" (1 John 3:4).

Most of the time, we face more than one lawful option. Then we must ask of each, "Which seems, in my fallen and fallible judgment, likely to bring better results?"

Every such choice involves trade-offs. Sometimes they're benign — do I buy the chocolate or the vanilla ice cream today, knowing I don't have space in the freezer for both? (But I could buy another freezer to accommodate both! But then maybe I couldn't pay my electric bill, and everything in both freezers would spoil!)

Always, benign or not, trade-offs involve choosing perceived benefits over perceived costs. Choosing the chocolate means going without the vanilla. Sometimes they involve choosing between more benefits and fewer benefits — the chocolate gives me more pleasure per bite. Sometimes they involve choosing between more costs and fewer costs — the vanilla costs 20 percent less.

It's that last case — choosing between more costs and fewer costs — that mirrors this year's presidential election.

To put it starkly, if I were in a situation in which I faced a choice between stopping a man with a machine gun from mowing down a hundred innocent victims and stopping a man with a handgun from shooting ten, and I couldn't do both, I'd choose to stop the man with the machine gun. That choice would have a trade-off — allowing the man with the handgun to shoot the ten. It would also have the effect of having saved a net ninety lives.

That's what the choice of the lesser of two evils means. So long as neither Jesus (the maximally good) nor Satan (the maximally evil) is on the ballot, the lesser of two evils exactly equals the greater of two goods, and in this fallen world that choice is inevitable.