Critical theory is not biblical justice, it locates evil in the wrong place: Tim Keller explains

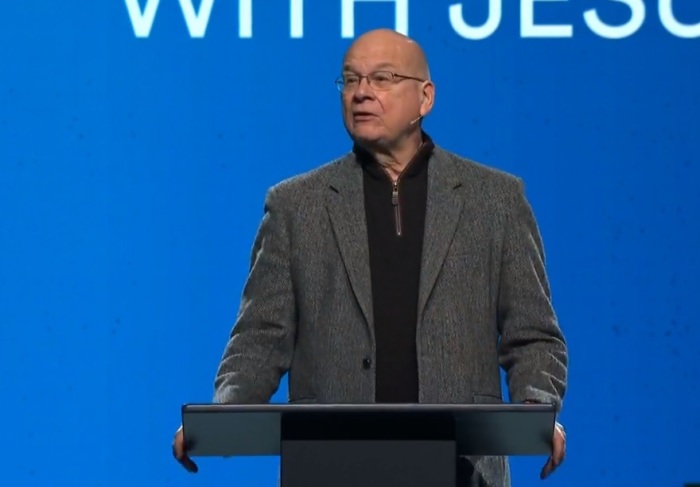

Acclaimed theologian Tim Keller recently addressed the issue of critical theory which has become popularized in some Christian circles.

In a lengthy essay published at Life in The Gospel, the former pastor at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan articulated the differences in the many theories of justice presently swirling in culture, including postmodernism.

"There have never been stronger calls for justice than those we are hearing today. But seldom do those issuing the calls acknowledge that currently there are competing visions of justice, often at sharp variance, and that none of them have achieved anything like a cultural consensus, not even in a single country like the U.S. It is overconfident to assume that everyone will adopt your view of justice, rather than some other, merely because you say so," Keller wrote.

Though the Bible established a comprehensive vision for justice, because of the failures of some contemporary Christians to see the work of justice as part of their vocation as followers of Jesus, secular models for justice have gained ground and are distorting Christian faith and practice.

Central to understanding what is truly just is sharing a common understanding of what it means to be human and why we were created.

"The secular view is that human beings are just here through chance. We are not here for any purpose at all. But if that is the case then there is no good way to argue coherently on secular premises and beliefs about the world that any particular behavior is wrong and unjust. Human rights are based on nothing more than that some people feel they are important."

Yet Scripture depicts the human world as a profoundly inter-related community and as such, those who are godly must live for the strengthening of the community, he continued, noting that this extends to how people deal with their wealth.

"To treat all of your profits and assets as individualistically yours is mistaken. Because God owns all your wealth (you are just a steward of it), the community has some claim on it. Nevertheless, it is not to be confiscated. You are to acknowledge the claim and voluntarily be radically generous. This view of property does not fit well with either a capitalist or a socialist economy," he explained.

The theologian extensively unpacked postmodern critical theory which has taken off in some quarters of evangelicalism. Resistance to critical theory has in part fueled the formation and launch earlier this year of a new network of theological conservatives within the Southern Baptist Convention who insist that the theory is diametrically opposed to the Gospel.

He elaborated that postmodernism is incoherent and that it holds that the explanation of every unequal outcome in power, wealth, and well being are never the result of individual actions or to cultural differences or to differences in human abilities, but only structural, systemic injustices in society. In this view, truth is impossible to know outside of its relationship to power.

"If all truth-claims and justice-agendas are socially constructed to maintain power, then why aren’t the claims and agendas of the adherents of this view subject to the same critique? Why are the postmodern justice advocates’ claims that 'This is oppression' unquestionably, morally right, while all other moral claims are mere social constructs? And if everyone is blinded by class-consciousness and social location, why aren’t they? Intersectionality claims oppressed people see things clearly — but why would they if social forces make us wholly what we are and control how we understand reality?" he offered.

"The Postmodern account of justice has no good answers for these questions. You cannot insist that all morality is culturally constructed and relative and then claim that your moral claims are not. This is not a flaw that only Christians can see, and this may therefore be a fatal flaw for the entire theory," Keller said.

Postmodern critical theory also holds that any evil is instilled in humans by society and any pathology can then be fixed by revamping social policy.

"But biblically we know we are complex beings — socially (both individual and social creatures made in the image of a Three-in-One God), morally (both sinful and fallen, yet valuable in the image of God), and constitutionally (we are equally soul-spirit and body). The reasons for evil and for unjust outcomes in life are multiple and complex," he said.

"The Bible teaches that sin is pervasive and universal. We are each members of a race or nationality that contains much unique common grace to contribute to the world. But every culture also comes with particular sinful idolatries. No race or people group is inherently more sinful than others. But in this postmodern view of justice groups are assigned higher or lower moral value depending on their power, and some groups are denied any redeeming characteristics at all. To see whole races as more sinful and evil than other races leads to things like the Holocaust."

The distinctly secular theory of justice locates evil in the wrong place, he added, seeing all injustice as occurring on a human level, demonizing human being instead of recognizing evil forces — "the world, the flesh, the devil" operating in every human being (Ephesians 6:12).

"Adherents of this view also end up being utopian — they see themselves as saviors rather than recognizing that only a true, divine Savior will be able to finally bring in justice. When dealing with injustice we do confront human sin, but in addition 'we wrestle not [merely] with flesh and blood” (Ephesians 6:12),'" he said.