Religious freedom is for Muslims too

Religious freedom must be for everyone, or we all suffer.

Last week, a Muslim on death row requested the presence of an imam at his execution. The state of Alabama denied this request even though it had allowed it for executed inmates who requested a Christian pastor. We add our voice to the Christian leaders who have condemned this act.

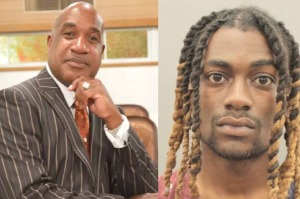

Domineque Ray was executed Feb. 7 for murdering a teen girl after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review his request for a religious accommodation. The court's conservatives, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, John Roberts and Clarence Thomas, who ostensibly were nominated partly due to their support for religious freedom, denied the request, while the court's liberals, Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elana Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, dissented.

In 1990, the Supreme Court ruled in Oregon v. Smith against a member of the Native American Church who sought a religious accommodation regarding his use of peyote, a banned hallucinogenic, as part of a religious ritual. A law that is neutral with regard to religion — banned people of all religions, not just the Native American Church, from using peyote — didn't violate the free exercise of religion, the Court reasoned at the time.

Both conservatives and liberals united in opposition to that court's "neutrality principle" and passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. They recognized that all of us were in danger of losing our religious freedom if the state could infringe upon our religious practice as long as its actions applied to all religious groups.

Instead of neutrality, RFRA codified an "accomodationist" principle. The government could still restrict your religious freedom under this principle, but to do so it would have to prove to a court that it had no other option. In the words of RFRA, there must be a "compelling governmental interest" and the government must use "the least restrictive means." Essentially, this means that the government will do its best to accommodate everyone's religious belief and practice, and will only restrict religious liberty when it has a really good reason to do so.

After Congress passed RFRA and the Supreme Court ruled it doesn't apply to state laws, many states passed their own version, including Alabama, which amended its constitution.

Alabama argued that Ray's imam hadn't gone through the training that the Christian pastors had gone through. But the accommodation principle implies the state will make extra effort to accommodate our faith. Alabama could've expedited the imam's application, or delayed the execution. If we allow our government to use "that would be hard" as an excuse, religious freedom is endangered for us all.

Kagan used the principles embodied in RFRA to support her dissent, joined by the court's other three liberals.

"To justify such religious discrimination, the State must show that its policy is narrowly tailored to a compelling interest," she wrote.

This is a welcome change from the liberal wing of the court. When the conservative Christian owners of Hobby Lobby asked for a religious accommodation under RFRA, those same four justices were in the minority. The five conservatives, three of which still sit on the court, were in the majority.

To secure religious freedom for all, we need consistency from the court. The religious freedom of Christians shouldn't depend on having a conservative majority; the religious freedom of Muslims shouldn't depend on having a liberal majority. In defense of the religious liberty embodied in the First Amendment, courts and other government officials must make the effort to accommodate the religious beliefs and practices of all.