Religious nonprofit group led by former US Amb. Sam Brownback says Chase closed its bank account

'What happens when they start de-banking pastors and Christian business people?'

A nonpartisan, faith-based nonprofit organization led by a former United States Ambassador for religious freedom says its Chase bank account was abruptly closed with little explanation.

The National Committee for Religious Freedom (NCRF), a 501(c)4 political action nonprofit whose stated mission is focused on “defending the right of everyone in America to live one's faith freely,” opened an account with Chase in April.

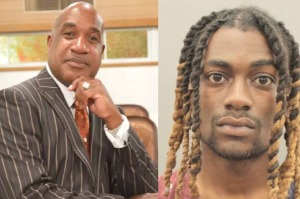

Sam Brownback, NCRF chairman and former U.S. ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom under the Trump administration, wrote in a piece published by The Christian Post that NCRF initially had a “very positive” experience with the bank.

But less than three weeks after it was opened, Chase informed NCRF on May 6 that the bank would be closing their account.

Brownback said there was “never an official cause given” when an NCRF official went to make a deposit into the account and a clerk said the account was closed.

According to Brownback, after NCRF Executive Director Justin Murff reached out for more information on the move, he was told the decision was made at the “corporate level.”

“It’s secret, it’s irrevocable, and that’s all the information we got,” added Brownback, who also served as a U.S. senator and governor of Kansas from 2011 to 2018.

After Chase employees initially told NCRF they were “prohibited from providing any explanations” for the move, the bank later said NCRF failed to provide requested documentation within 60 days — even though the account had only been open for 20 days.

After looking further into the issue, a representative from the Chase executive office identified only as “Chi-Chi” contacted Murff and explained that it might be possible to continue the business relationship if NCRF could provide some further details about the nonprofit’s political activities.

Murff told CP that included providing a list of donors who have given more than 10% of NCRF’s operating budget, a list of candidates NCRF intends to support and the criteria which NCRF uses to decide whom it supports politically.

If NCRF could provide those to Chase, Murff said he was told the bank “could potentially consider reopening the account.”

Brownback — who described the Chase leadership board as a “very reputable” group — said he has “no idea” whether the decision was made by an individual or collective group to close the NCRF account.

“Does Chase ask every customer what politicians they support and why before deciding whether or not to accept them as a customer?” Brownback wrote.

Ultimately, NCRF was able to open a new account at a different bank, but not after facing “unexpected operation and financial challenges” following the letter from Chase.

Two spokespeople for Chase did not return a request for comment from CP.

Brownback said after the ordeal, he believes it’s time for Congress to “hold a series of hearings investigating business, particularly big corporations, that exclude people and try to find out why.”

NCRF has also launched its “#ChasedAway” campaign to hear from other faith-based organizations on whether they have had similar experiences.

“On what basis are these institutions doing this?” he added. “I just never expected it would happen to me or this organization.”

But for Murff, the experience has raised troubling questions about whether this trend could continue — and potentially worsen — in the future.

“If they can ‘de-bank’ the NCRF, a multi-faith religious nonprofit, what happens when they start 'de-banking' pastors and Christian business people?” Murff asked.