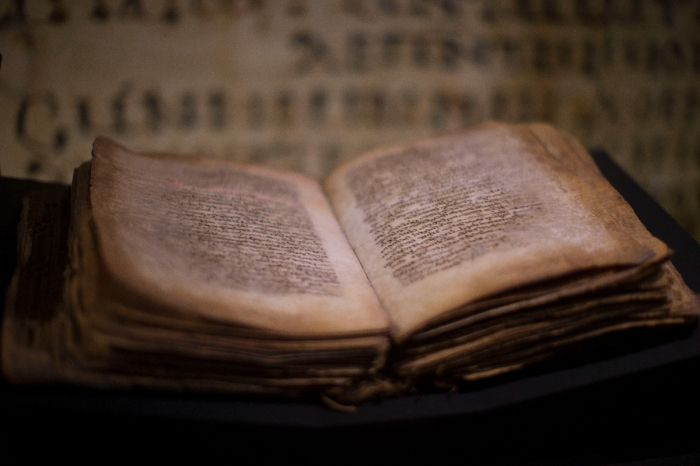

Scientist discovers 'erased' 1,750-year-old New Testament translation using ultraviolet photography

A scientist claims to have discovered a hidden ancient translation containing portions of the Gospel of Matthew which are said to be the only known "remnant of the fourth manuscript that attests to the Old Syriac version" of the Gospels.

The researchers, including medievalist Grigory Kessel of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW or Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften), used ultraviolet photography to find the ancient translation hidden underneath three layers of text.

The study, published last month in the journal New Testament Studies, features an interpretation of Mattew 11:30 to Matthew 12:26, originally translated as part of the Old Syriac translations nearly 1,500 years ago.

According to the British Library, Syriac was a dialect of Eastern Aramaic used by the Church in Syria and several countries in the Middle East from the first century until the Middle Ages. Although it was written in the same alphabet as Hebrew, the Syriac language has its own unique characters.

"As far as the dating of the Gospel book is concerned, there can be no doubt that it was produced no later than the sixth century," the study reads. "Despite a limited number of dated manuscripts from this period, comparison with dated Syriac manuscripts allows us to narrow down a possible time frame to the first half of the sixth century."

According to a statement released by OeAW earlier this month, the discovered text was made in the third century and copied in the sixth century. More than 1,000 years ago, a scribe in ancient Israel erased a book of the Gospel inscribed with Syriac text to reuse it, as the parchment was a scarce resource in the desert in the Middle Ages and was often reused.

"The tradition of Syriac Christianity knows several translations of the Old and New Testaments," Kessel stated. "Until recently, only two manuscripts were known to contain the Old Syriac translation of the gospels."

One of those fragments is kept at the British Library in London. The second fragment was discovered as a "palimpsest," or reused manuscript that still bears traces of its original form, in St. Catherine's Monastery at Mount Sinai.

The fragment identified by Kessel offers a "unique gateway" to an early phase of the "textual transmission" of the Gospels.

"For example, while the original Greek of Matthew chapter 12, verse 1 says: 'At that time Jesus went through the grainfields on the Sabbath; and his disciples became hungry and began to pick the heads of grain and eat,' the Syriac translation says: '[...] began to pick the heads of grain, rub them in their hands, and eat them," the statement noted.

Claudia Rapp, the director of the Institute for Medieval Research at the OeAW, praised Kessel for the discovery, crediting the researcher for his "profound knowledge" of old Syriac texts and script characteristics.

Rapp estimated that the Syriac translation was produced at least a century before some of the oldest surviving Greek manuscripts, including the Codex Sinaiticus. The Codex Sinaiticus is a complete text of the Gospels believed to be older than the fourth century.

"This discovery proves how productive and important the interplay between modern digital technologies and basic research can be when dealing with medieval manuscripts," Rapp stated.

In February, The Christian Post reported on the upcoming auction of the Codex Sassoon in May, which is reportedly the earliest single codex containing all the books of the Hebrew Bible. Created circa 900, the book consists of 24 books divided into three parts.

The Hebrew Bible is foundational to three Abrahamic religions, Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The 24 books contain the canonical Hebrew Scriptures: the Torah, the Nevi'im and the Ketuvim.

Sotheby's, the fine arts company auctioning the book, suggests it could sell for up to $50 million at the scheduled auction in New York. Before the auction, the manuscript is touring several major cities, including Tel Aviv, Israel, Dallas and Los Angeles, providing the public with an opportunity to view it.

Samantha Kamman is a reporter for The Christian Post. She can be reached at: samantha.kamman@christianpost.com. Follow her on Twitter: @Samantha_Kamman