Still Evangelical? Christian Scholars Analyze Evangelicalism Under Trump in New Book

"Am I still evangelical?" That is a question many believers in the United States are asking themselves these days.

In the wake of the election of President Donald Trump in November 2016, there has been widespread contention, disagreement and confusion surrounding the meaning of the word.

A word that once had a theological and spiritual connotation has seemingly become, in the eyes of many, a political term associated almost exclusively with white evangelicals and their staunch support of social conservative policy stances on issues like abortion and marriage, and their embrace of controversial political candidates such as Trump and Alabama's Roy Moore.

For other evangelicals, such as those of color and those who lean to the liberal side of the political spectrum on issues such as the environment, immigration, poverty and gender equality, many are attempting to distance themselves from the "evangelical" label because they feel the term has been "hijacked" by the media's portrayal of American evangelicalism.

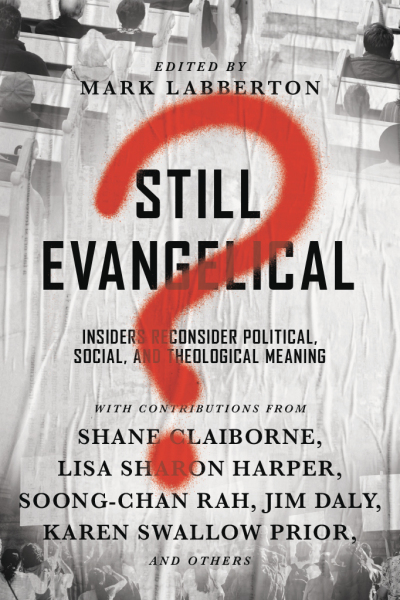

In light of the current societal confusion surrounding the term "evangelical," InterVarsity Press has released a new book that compiles a collection of essays written by 10 evangelical scholars analyzing the state of evangelicalism in the Trump age.

"Evangelicalism in America has cracked, split on the shoals of the 2016 presidential election and its aftermath, leaving many wondering if they want to be in or out of the evangelical tribe," Mark Labberton, president of Fuller Theological Seminary in California, wrote in the book, Still Evangelical? Insiders Reconsider Political, Social, and Theological Meaning.

As a number of well-known evangelicals have come out in the past year and publicly disassociated themselves from their evangelical identity or have had cause to "rethink" their evangelical identification, the new book features essays from evangelical insiders such as Focus on the Family President Jim Daly, North Park University professor Soong-Chan Rah, Christian social activist and author Shane Clairborne, and Liberty University English professor Karen Swallow Prior, among others.

"I am evangelical because evangelical is a theological term that has historically and still refers to the way that one understands the Gospel and its application in one's life. Evangelical as a theological term hasn't changed and my theology has not changed," Prior told The Christian Post.

"Evangelicalism has become linked to a certain political posture within 21st-century America. But evangelicalism is 300 years old. It's worldwide and its much bigger than this moment in 21st century America."

According to the National Association of Evangelicals, the word evangelical does not refer to one's political leanings or one's skin color, but rather is a term that classifies all Christians — whether white or black or Democrat or Republican — who believe in four basic truths:

- The Bible is the highest authority for what I believe.

- It is very important for me personally to encourage non-Christians to trust Jesus Christ as their Savior.

- Jesus Christ's death on the cross is the only sacrifice that could remove the penalty of my sin.

- Only those who trust in Jesus Christ alone as their Savior receive God's free gift of eternal salvation.

As Prior notes in her essay in the book, this is not the first time in American history in which those who subscribe to the theological tenets of evangelicalism have disagreed on some of the nation's hottest social issues of the day.

"Like all human works and movements, evangelicalism is far from perfect. In both its history and its present state, there is perhaps too much of the taint of entrepreneurialism, progressivism and individualism," Prior wrote. "That some leading evangelicals supported slavery centuries ago while others didn't demonstrate that uniformity, unity and infallibility are not characteristics of evangelicalism."

Like other social movements, evangelicalism is not monolithic and has largely shifted along with cultural tides, Prior explained.

"As the culture shifts and carries the boat of evangelicalism with it, we've got to look at the North Star and change course accordingly and it doesn't happen instantaneously," Prior said.

Labberton, the editor of the new book, argued in his introduction that evangelicals are more likely to be influenced politically by their "social location" than their theology.

"Right now, evangelical is one of those labels that is up for grabs because it's been taken and used both by the media and various evangelical voices to mean something that is often quite specific and in many people's minds, antithetical to the Gospel itself," he told CP.

Claiborne, who helped found the Red Letter Christians movement and founded The Simple Way community in Philadelphia, feels evangelicals have an "image crisis" on their hands, "whether it is deserved or not."

"When people hear the word evangelical, it conjures up an image of folks who are anti-gay, anti-feminist, anti-environment, pro-guns, pro-war, and pro-capital punishment. We often look very unlike Christ," Claiborne wrote in his essay titled "Evangelicalism Must Be Born Again."

"One does have to wonder if the evangelicals of old who were so passionate about peace and caring for the poor and ending slavery would even recognize the evangelicalism of today," he added. "If alive today, would they be evangelical?"

As exit polls show that 81 percent of self-identified white evangelicals and born-again Christian voters voted for Trump in the 2016 election and 80 percent of evangelical voters voted for Moore in last year's Alabama Senate race, Prior makes the case in the book that those quitting evangelicalism today are seemingly doing so due to the "embarrassment and shame over the way evangelicalism is reflected in distorted glass held up by media and poorly designed polls."

Many research polls have flaws in how they categorize evangelicals. For example, many polls that measure evangelicals as a voting bloc don't include non-white evangelicals in the "evangelical" category. Additionally, many polls ask respondents to simply identify themselves as "born-again" or "white evangelical" without really qualifying their theological beliefs as being authentically evangelical. As has been reported, such polling could lead to skewed results.

"I am not really blaming the media. It's a category that exists and they don't understand it. As evangelicals, we are very loosely defined. I think it's an inherent problem within the evangelical identity and practice that the media and pollsters are not all that well equipped to solve," Prior said. "It's just magnified and that's hard, but I think that magnification and having our identity and appearance distorted through the funhouse reflection of the media could actually be helpful."

As white evangelical leaders who have served as informal advisors to the Trump administration received much flack last week for their defenses of Trump's alleged affair with porn star Stormy Daniels in 2006, Prior said that the public distortion of evangelicalism can be helpful because it could allow evangelicalism as a whole to "look at those distortions and see where we need some self-correction and self-examination."

Prior, who serves as a research fellow with the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, argues that what we see today with conservative evangelicals and their staunch support of Trump could be the marks of an "overcorrection" that began in the 1970s and 1980s.

"I think what we saw evangelicals do in the '70s and '80s was to overcorrect the separatist impulse from the branch of evangelicalism that was rooted in fundamentalism. They overcorrected the withdrawal from culture by becoming overly married to politics," Prior said. "Now we are seeing the limits of that. I think we are in another correcting mode."

"I think we just have to have a better understanding of the proper relationship of our individual faith and the place of the Church to politics," she added. "The pragmatism that necessarily defines politics, it works in politics but it is lethal to the Church. I think we have to be careful to not take one category of culture and confuse it with another. How we exist as citizens in the Kingdom of God doesn't really operate according to the same principles as being a citizen in America."

Rah, the professor of church growth and evangelism at North Park University in Chicago who has been involved in multiethnic ministry and a proponent of racial reconciliation within the Church, told CP that "the evangelicalism that formed me in that name doesn't exist in that form" anymore.

"What drew me to the evangelical movement in the first place is my experiences in places like Intervarsity, through my denomination at the Evangelical Covenant Church, through my interaction with wonderful organizations like World Vision. What I have seen is an active, vibrant faith that emerges out of a spiritual depth," Rah told CP.

"I don't know if I need to bring that name back but I certainly want to bring back the passion, the forms and the expressions. I still want to have the real respect for Scripture that my evangelical seminary education gave me. I want to have the care for the poor that my relationship with World Vision has produced. I want to have concern for the 'very least of these' that my engagement with Sojourners and CCDA has produced."

Rah argues in his essay "Evangelical Futures" that because of the increasing racial diversity in the United States, Americans may be seeing a revival of Christianity in a "vastly different form."

According to Rah, a new revival of Christianity could be exemplified by the growing "presence of Asian Americans in evangelical seminaries, increased church-planting efforts in evangelical denominations by Latinos, the replacement of aging white churches with immigrant churches, and an increase in participation in white megachurches by African-Americans."

However, Rah contends that there is a barrier between white evangelicals and evangelicals of minority status, saying that over the years, non-white expressions of U.S. evangelicalism "are often portrayed as inferior to the success formula put forth by many white evangelicals in mainstream U.S. Christian culture."

"Many Korean American immigrants gather at five every morning to pray at their church before embarking on a 12-hour workday. But this expression of spirituality may be ignored among the latest evangelical church fads, because it is spoken in a foreign language or in English with an accent," Rah said. "African-American evangelicalism is considered an inferior brand of evangelicalism, with its emphasis on justice and race issues discounting its leaders from key positions of leadership."

Prior agreed.

"The color and race divide within evangelicalism is one of the things that has existed since its beginnings and continues to exist today," she said. "This painful moment that we are going through is exposing something that has been evident to our brothers and sisters of color but less evident to the majority culture. We need to take advantage of this moment to learn what these fault lines have been all along."

Labberton told CP that "the community of God's people is meant to be an expression of God's own design and creativity, which includes and welcomes people of every tribe, tongue and nation."

"Often times, evangelicalism functions sociologically as a white tribe," he said. "Part of why this book is written and part of why evangelicalism is being contested today is because that fact has been exposed by the election to such decree that it causes people of color to understandably ask, 'If it is such a white movement, do I have any place in such a movement that is predominantly white?"

Still Evangelical? also features writings that focus on topics such as unity, theology and orthopraxis in global evangelicalism, evangelical identity and mission, and the "hope for a next generation."