‘The Next Jihad': Evangelical leader, rabbi warn about 'Christian genocide’ in Africa

The rise of violent extremist groups throughout Africa, as well as the constant attacks against Christian communities in the continent’s most populated country, has religious leaders fearful that “the next jihad” is underway as world leaders seem to be rushing to address the problem.

“I know one thing has never really changed: No one gives a damn about Africa except for their natural resources or if there is going to be a big party because there is a peace treaty being signed,” said Rabbi Abraham Cooper, director of the global social action agenda of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a leading Jewish human rights organization with over 400,000 family members.

“That’s just the truth and it’s a terrible truth. It might be one of the vestiges, frankly, of colonialism.”

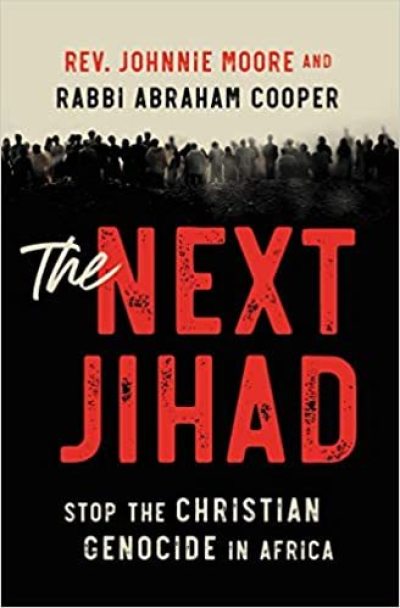

Cooper teamed up with Rev. Johnnie Moore, a commissioner on the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom and president of the Congress of Christian Leaders, to author the new book The Next Jihad: Stop the Christian Genocide in Africa.

The book was written after the unlikely duo traveled together to Nigeria earlier this year to meet with dozens of Christian victims of terrorism from five different regions.

In recent years, Nigeria, the continent’s richest country, has dealt with the rise of Islamic terrorist groups in the northeast (Boko Haram and the Islamic State West Africa Province) and an increase of deadly attacks on farming communities carried out by militarized radicals from the Fulani herding community.

In the past few years, it’s been estimated that thousands of Christians have been killed while millions of Nigerians have been displaced from their communities. Some human rights groups have warned that attacks against Christian communities in Nigeria have reached the standard for genocide.

“[We want] to help people really feel the problem and understand it enough to do something about it,” Moore, an evangelical human rights advocate, told The Christian Post about the purpose of the book. “It was Rabbi Cooper who initiated the trip and encouraged me and us to go together to shine a light on what was happening there. It felt like deja vu to me because back in 2014, the Weisenthal Center was the first organization of any kind that recognized what ISIS was doing to Christians and Yazidis in Iraq was genocide.”

“Where my mind was when we were writing the book right after our trip, 10 days before the world started shutting down because of COVID, I thought this could be the next jihad,” Moore continued. “I since come to realize that it is the next jihad right now. It is not just Nigeria. It is the countries around Nigeria. It is a quickly escalating problem.”

Outside of Nigeria, the growing presence of Islamic extremist groups and increasing attacks have plagued other regions of Africa and caused mass displacement.

Those regions include the Sahel, where hundreds of thousands have been displaced amid escalating terror attacks in the last two years in Burkina Faso, as well as East Africa, where al-Shabab terrorists are attacking citizens in Somalia and Kenya. In southern Africa, over 300,000 people have been displaced in Mozambique amid a stark increase in radical Islamic extremist attacks in the northern part of the country in recent years.

While acknowledging that the spread of terrorism and violence in Africa after the fall of ISIS in Syria and Iraq is a continent-wide problem, much of the book’s focus is on Nigeria as both leaders see the country as being a continental leader when it comes to its size and influence.

“It has the 10th largest oil reserves in the world, it is the most populated country in Africa,” Moore explained. “It has the largest economy in Africa. It is surrounded by countries with terrorist insurgencies. If anything goes the wrong way, the Syrian crisis will feel like a distant memory compared to the catastrophe that the failure of West Africa could actually happen because of neglecting the situation in Nigeria.”

But in Nigeria and even among some U.S. diplomats, the debate on violence in Nigeria is complicated, especially when it comes to the rise of Fulani extremist attacks on predominantly Christian farming villages in the country’s Middle Belt.

On a regular basis, reports emerge of overnight attacks carried out on farming villages in which people are slaughtered, homes are burned and farmlands are confiscated.

“One of the important things to understand that it is not just Boko Haram and ISIS in West Africa now,” Moore said.

“But because the government now has neglected dealing with these people, you have militarized Fulani tribesman. We are very careful to make it clear that Fulani are the largest tribe in Africa — almost 20 million. Not every Fulani is a terrorist. But because the government hasn’t dealt with the terrorism in the northeast, you have terrorists among the Fulani who are now killing more people than Boko Haram ever had in the center part of the country, which happens to be where the Christians and the oil is.”

The Anambra-based International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law estimates that at least 812 Christians were killed by Fulani radicals in the first half of 2020 by radical herdsmen.

While human rights advocates have accused the Nigerian government of not doing enough to protect its citizens from Fulani attacks, talk about how the international community should respond to the crisis has been “deflected” by a debate about what role religion is playing in the Fulani attacks, the authors explained.

While the Nigerian government has maintained that the conflict is less about religion and is just a continuation of a decades-old resource conflict between herders and farmers, Christian victims and advocates contend that there are strong religious overtones at play in the violence that should not be ignored, especially when attackers are screaming “Allahu Akbar” as they slaughter villagers and burn down houses.

In the book, Moore and Cooper recalled a meeting they had in February with U.S. Ambassador to Nigeria Mary Beth Leonard in which they discussed the religious aspects of the violence throughout the country.

“She denied that it was at all about religion and described the conflict as ‘fundamentally a resource issue,’” the book states. “Religion was, according to Ambassador Leonard, only relevant as it served as a potential accelerant to conflict. She left us with the impression that people like us, by speaking up for victims of religious persecution, were part of the problem. We found this to be hugely alarming.”

Cooper pointed out that while the Nigerian military has the capacity to stop the violence, the military has not been or willing or able to do so. The authors believe that the U.S. and United Kingdom governments should do more in their power to pressure the Nigerian government to protect its citizens.

”The goal is to get these two governments to sort of get past the reflective and deflective discussions about whether it is just tribal and religion,” Cooper stated. “We don’t want to demonize Nigeria as a failed or lost state, it is not there yet. It is too big and too important to fail. We need American diplomats, U.K. diplomats and others to stop putting blinders on because they just don’t want to go there when it comes to religion. That is a huge mistake. You can’t treat cancer unless you can fully identify the nature and scope of that cancer."

The book was released just weeks ahead of the U.S. presidential election last month.

“We believe that whoever is sitting in the Oval Office in January and whatever the number counts are in the House and Senate, the issue of Nigeria — and specifically the genocide that is underway there against Christians — will have to be an issue that is dealt with by the United States,” Cooper contended, “not only because of religious freedom and all the rest but also because of the terrorist players that are operating in the neighborhood and expanding their operations.”