Reckoning With the Peaceable Kingdom: A Review of Disarming the Church

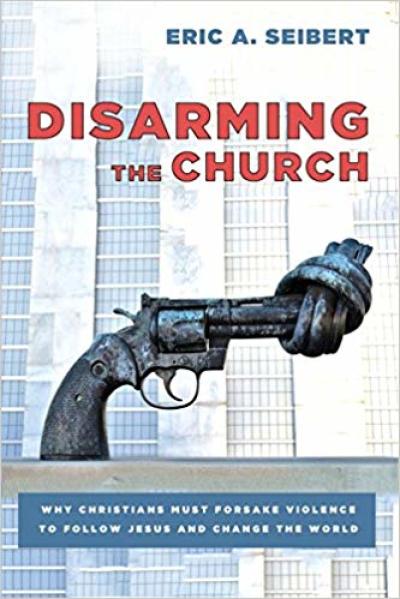

Eric A. Seibert. Disarming the Church: Why Christians Must Forsake Violence to Follow Jesus and Change the World. (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2018.)

Carl Norden was a devout Christian. So when he developed the Norden bombsight, it was with the intent of increasing the accuracy of aerial bombing to the end of decreasing the resulting collateral damage wrought by war. In short, the bombsight was meant to embody Norden's Christian values lived out on the field of battle.

Unfortunately, while the bombsight promised deadly accuracy under ideal conditions, the theater of war rarely offers ideal conditions. As a result, the bombsight never lived up to its promise ... though it was accurate enough on the day it was used to detonate an atomic bomb over Hiroshima.

The sad story of Carl Norden provides a salutary warning for all Christians who seek to live out their cruciform discipleship in service of war and violence. If I had more time, I could give you other examples such as the story of Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, a follower of Jesus whose hatred of executions led him to propose an ill-fated means of making them more humane.

But what, exactly, is the lesson? Do these examples simply offer a caution to Christians inclined to pragmatically adapt their convictions to realpolitik? Or is the real lesson that Christ calls us to lay down our weapons and set aside our violent inclinations even as we take up our cross?

An Overview

In his new book Disarming the Church, biblical scholar Eric Seibert defends the second view: to follow the Prince of Peace, he insists, requires a radical and categorical rejection of violence.

Disarming the Church is divided into four parts. Seibert begins in Part 1 (chapters 1-4) by summarizing the church's problematic relationship to violence. Next, Part 2 (chapters 5-9) is devoted to presenting a case for non-violence based on the witness of the New Testament, and the life and teachings of Jesus in particular.

While Part 2 is the heart of the book, Seibert also recognizes the critical importance of narrating new ways to live peaceably. And so, he dedicates the final two parts of the book to exploring new ways of thinking with a range of practical alternatives to violence (Part 3; chapters 10-12) and a new vision for living non-violently every day (Part 4; chapters 13-17).

Defining Violence

If you're going to argue that violence is incompatible with Christian discipleship, you should be clear as to what, exactly, violence is. Seibert recognizes this point and so he offers the following definition:

"Violence is physical, emotional, or psychological harm done to a person by an individual(s), institution, or structure that results in serious injury, oppression, or death." (10)

Unfortunately, this definition is inadequate on two counts. To begin with, it is too restrictive insofar as it limits violence to injurious actions visited upon persons, a stipulation which would exclude human beings who are not (or not yet) persons (e.g. fetuses).

Admittedly, that problem can be fixed easily by replacing "person" with "human being". More problematically, the definition intentionally excludes injurious actions against non-human animals or natural systems and structures. To be sure, there is a logic at work: Seibert's definition of violence in terms of harm inflicted upon human persons reflects his focus in the book. But while Seibert has every right to limit the scope of his interest, the proper way to do this is by stipulating that you will limit your discussion to intrahuman violence, not by defining violence as intrahuman violence.

This brings me to the second problem: Seibert's definition is also too rigorous. The point is illustrated with his unqualified condemnation of spanking:

"Regardless of how 'lovingly' it is done, or how controlled the parent may be while doing it, spanking is a form of violence." (238)

While I agree with Seibert that spanking is violent, in most instances it is not sufficiently intense to inflict the serious injury, oppression, or death required by Seibert's definition of violence. As a result, by Seibert's own definition, most instances of spanking are not, in fact, violent. This shows us that Seibert's definition of violence is too restrictive since it fails to recognize relatively mild examples of violent behavior.

After all that, you might be wondering how I would define violence. For the purposes of this review, I'm content to borrow Justice Potter Stewart's famous statement on obscenity: we know it when we see it. But whatever our definition, we should recognize that violence comes in degrees of intensity ranging from mild (e.g. spanking) to severe (e.g. killing) and it can be inflicted not only on human persons (or beings) but also on other living creatures and living systems.

Violence is Bad

Part 1 is dedicated to identifying the church's relationship with violence and the problematic nature of violence. Seibert avoids recounting a long history of crusades, pogroms, witch burnings, battles, and the like, opting to focus instead on the current state of the church. For example, he notes how the church in the United States is statistically more likely to support war and torture than the general population (18, 19). He also recounts examples of the church's heightened rhetoric against various out-groups such as Muslims, atheists, and gay people.

Ultimately, the church's acceptance of violence is rooted in what Jim Forest refers to as "the Gospel according to John Wayne" (34) according to which one deals with violence by way of more violence. In short, the church has bought into the myth of redemptive violence.

And it is a myth, or so Seibert argues in chapter 4, "The Truth about Violence: It's All Bad." In this chapter, Seibert amasses evidence that violence begets more violence, it escalates dangerous situations, it adversely affects innocent parties, and it has wholly negative psychological and emotional impacts on those who participate in it such as the "moral injury" of soldiers (54). The essence of the chapter is found in the sobering conclusion of one soldier:

"The biggest lie I have ever been told is that violence is evil, except in war .... My government told me that ... I came back from war and told them the truth–'Violence is not evil, except in war .. violence is evil–period.'" (Cited in 59)

The Prince of Peace

In part 2, Seibert makes a case for peace based on the New Testament (though he also briefly references OT sources for peace (61-3)). The heart of his case is the life and teaching of the Prince of Peace as surveyed in chapter 5. In the Sermon on the Mount, Christ taught his followers to be peacemakers (Mt. 5:9), to love our enemies (5:38-48), and to follow the Golden Rule (7:12).

While some people seem to view the pacifistic response as milquetoast discipleship, Seibert helpfully explains how actions like turning the other cheek, in fact, constitute a bold assertion of personal dignity and resistance to unjust oppression (66-67). In other words, the rejection of violence does not mean one is left to acquiesce in the face of oppression. Rather, it challenges us to pursue a courageous confrontation of evil and a prophetic anticipation of a better world.

Jesus modeled the peaceable kingdom in his own ministry. Throughout his life, he rejected violence and preached forgiveness (see, for example, Luke 9:51-56; 22:47-53; John 7:53-8:11), culminating, of course, in his atoning death on the cross. And we are called to take up our crosses in emulation of him (Luke 9:23).

Anybody who has spent any time debating these topics knows that critics of pacifism have a list of go-to texts in which Jesus seems to adopt a more positive attitude toward violence. Seibert offers a rebuttal to those various texts in chapter 6. For example, Jesus is recorded in Luke as saying "the one who has no sword must sell his cloak and buy one." (22:36) Surely this text shows that Jesus did not accept pacifism?

No, Seibert insists, it doesn't. Instead, he argues that the passage is best interpreted figuratively:

"By telling his disciples they should now take a purse and a bag, and should buy a sword if they do not have one, he is informing them, albeit figuratively, that grave dangers lie ahead. He is not giving them a laundry list of items to acquire..." (89, emphasis added)

At first blush, this might seem to be a strained response: if Jesus truly was a pacifist why would he use the image of wielding a sword to warn of hard times ahead? That said, Seibert points out that immediately after this curious direction, Jesus rebukesPeter for using his sword (Luke 22:50), a point that would seem to support the figurative interpretation of the text.

Seibert also addresses Jesus' rhetorical violence against the scribes and Pharisees. While he concedes that Jesus' language can be harsh, Siebert stresses that we need to understand Jesus in his historical context:

"We should not expect Jesus to sound like a contemporary peacemaker or nonviolent practitioner. Nor should we evaluate Jesus' rhetoric by modern ethical standards and use those to accuse Jesus of being verbally violent." (91)

While Seibert is right to note that in general, we should interpret people as creatures of their times, this is not how Christians historically view Jesus. Rather, they view him as the perfect God-man who exemplifies proper behavior for all time. And thus, if Jesus visits upon his opponents rhetorical barrages which are inflammatory if not violent, one cannot help but wonder whether this provides a principled basis for Christians to do so as well.

Narrating Peace

The biggest challenge to peace is probably the fact that people don't believe true change can take place without violence. Siebert takes direct aim at that lingering belief in part 3. For example, he cites a major study of social change in the twentieth century which provides a striking statistic: "between 1900 and 2006, nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts." (185, emphasis Siebert's) Seibert even notes how non-violence could provide a proper response to the Nazis (187 n.).

Statistics are suggestive, but to really change people's thinking one needs story. As Seibert puts it, "stories are powerful. Stories engage our affect, and affect is critical for storing things in our brain and moving us to action." (9) As a result, he weaves several stories into his narrative of people who rejected violence and embraced the way of peace. Many of those stories inspire the hope that peaceable living is a realistic possibility. Rather than summarize some of those moving accounts to you, I'll direct you to CBC radio's challenging story, "How one woman came to forgive the man who murdered her father." If you are moved by that story, then it's a safe bet that you'll love Seibert's book.

The last half of the book is also packed with practical tips for pursuing a peaceful mindset. In chapter 15 Seibert offers a treasure trove of reflections on non-violent parenting. He observes, for example, that the closer war toys are to reality, the more problematic they become. Thus, for example, the pacifist parent might permit play with the cartoonish Masters of the Universe but not the truer-to-life G.I. Joe series (244).

While I found many of these suggestions helpful, at times Seibert's suggestions appear a bit pedantic and susceptible to the charge of virtue signaling. (Think, by analogy, of the vegetarian who never misses the chance to talk about the suffering of farm animals when you're simply trying to enjoy your hotdog at the baseball game.) For example, he suggests a parent might respond to violence in video games by offering some pacifistic commentary:

"'Wouldn't it be really cool if there was a way to make friends with the ogre rather than destroying him?' Or, 'Wouldn't it be neat if you could win the game by talking out your differences rather than shooting at each other?'" (242)

Um, yeah, maybe. But the typical kid is going to reply, "Dad, can't I just play the game?" and at some point, I'm inclined to agree with him.

Conclusion

Disarming the Church provides an eloquent and impassioned defense of pacifism. What is more, it is thoroughly grounded in reality as is evidenced in the multiplicity of eminently practical proposals for pursuing a peaceable existence.

Having said that, I find myself unable to offer an unqualified endorsement of the book's central thesis. My problem can be illustrated by the definition of violence that frames the discussion. You see, by this definition, chemotherapy is violent since chemotherapy often produces significant physical, emotional, and/or psychological harm in the individual (including, but not limited to a compromised immune system, fatigue, hair loss, and infertility). If I accepted Seibert's definition of violence, I'd be obliged to say that since all violence is bad, it follows that chemotherapy is bad.

It's important to understand that this problem cannot be dealt with by a simple fix like switching human person to human being. Rather, in my estimation, it goes to the core of the pacifistic thesis, because it seems to suggest that there are cases where violence is justified, such as in the case of the chemotherapeutic treatment of cancer. And if violence is justified in that case, one must consider whether it might be justified in other instances as well. Insofar as this remains an open question, it constitutes a significant objection to Seibert's thesis.

This leads me to a more specific concern. Seibert's pacifism constitutes a Christ-against-culture model which secures the church's faithful, prophetic witness at the apparent cost of societal engagement. But this is a significant cost to pay. For example, while Seibert observes that the threat of the police can be a deterrent to violence (172), he does not explicitly grant the possibility that Christians might be part of this deterrent force given that the police officer must be open to the use of violence if required. Does this mean that Christian discipleship requires withdrawal from participation in all law enforcement? By the logic of Seibert's argument, it would seem so. But some Christians will find this societal withdrawal to constitute an unacceptable consequence of pacifism.

I raise these issues not as refutations of Seibert's thesis but rather as spirited reactions to it. The point to keep in mind is that they are reactions which are stimulated by a book which offers an undeniably powerful defense of its central thesis. I may not agree completely with the core thesis of Disarming the Church, but I am most definitely challenged by it, as will be all Christians who commit to reading this eloquent treatise on the peaceable kingdom.

You can order a copy of Disarming the Church here.

Thanks to Cascade for a review copy of the book.