‘No other gods before me’: The first commandment’s national significance

The foundation of any community is built upon the rule of law. The Ten Commandments serve as the essential framework without which the formation and maintenance of a nation becomes impossible. The commands provide the fundamental principles of self-restraint and self-discipline, voluntarily accepted by the people. These commandments are not just religious edicts; they are vital laws that underpin nationhood and the very essence of democracy. Without these guiding principles, no group of people can truly come together to form a cohesive and functioning country characterized by peace, prosperity, justice, and integrity.

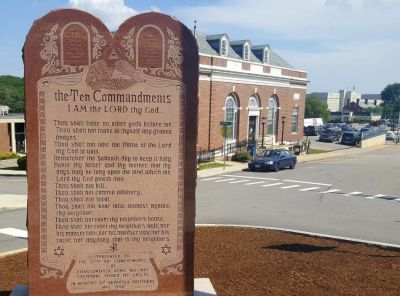

Two tablets of divine guidance

Traditionally, the Ten Commandments are seen as being divided into two sections, symbolized by the two tablets of stone on which God inscribed them. The first tablet contains four commandments that govern our relationship with the Lord. Those who love God above all will willingly follow these directives. The second tablet comprises six commandments that guide our interactions with others. By loving our neighbors as ourselves, we readily adhere to these rules.

Religious observance and secular law

The first four commandments pertain to one’s relationship with the Lord and are typically not required by secular law, nor would we want them to be. These commandments address religious observance and devotion, which are generally considered matters of personal faith rather than legal obligation.

People cannot be coerced into worship. True worship arises from sincere belief, from the heart, and not from conforming to the actions of others. It is not the government’s role to direct people’s worship experiences. Jesus noted the ideal for worship when He told the woman at the well:

“But the time is coming — indeed it’s here now — when true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and in truth. The Father is looking for those who will worship him that way. 24 For God is Spirit, so those who worship him must worship in spirit and in truth” (John 4:23-24).

The last six commandments, however, relate to social behavior and ethical conduct, and many of them are indeed reflected in laws across various societies. These include prohibitions against murder, theft, and bearing false witness, among others. These principles are relatively universal and often legislated to maintain social order and justice.

Ethical directives and their consequences

Some might argue that the 5th and 10th commandments, “Honor your father and your mother” and “You shall not covet,” are more like moral and ethical directives that are not easily legislated but if not followed have devastating consequences. Failing to honor one’s parents can lead to disregarding or disrespecting other important authority figures in life, which can result in personal destruction and cultural chaos. Coveting, or desiring what belongs to others, pertains to one’s inner thoughts and desires and is essentially impossible to legislate. Nevertheless, the internal act of coveting can be the impetus behind murder, adultery, stealing, and bearing false witness.

Interconnected commandments

Critical to one’s understanding is that although these two sections of the Ten Commandments emphasize different aspects — one vertical (pertaining to our relationship with God) and the other horizontal (pertaining to our relationships with others) — they are interconnected and mutually necessary.

Jesus stressed this connection when he summarized the entirety of the Law and the Prophets with two commandments: to love God with all one’s heart, soul, and mind, and to love one’s neighbor as oneself (Matthew 22:34-40; Mark 12:28-34; Luke 10:25-37).

In his book, The Ten Commandments: The Law of Liberty, Taylor G. Bunch eloquently explains:

“Spiritual vision illuminates the law, and obedience to the law increases spiritual vision until its revelations are wonderful. Viewing the decalogue under the magnifying glass of spiritual vision convinces us that it is so ‘exceeding broad’ that it embraces ‘the whole duty of man,’ and that the two tables which set forth man’s duties to his Creator and to his fellow man ‘hang all the law and the prophets.’” [1]

Thus, the first commandment, “You shall have no gods before me,” is not something that should be required by legislation. However, if it is not followed from the heart, the strength and power to live by the other commands are significantly diminished, if not destroyed. The law of God is a reflection of the Creator’s character. For humanity, which is made in the image of God, to flourish, the one and only true God must be known, acknowledged, and honored. Without a central focal point, without a point of spiritual and moral reference, on which society has consensus, serious divisions arise, leading to competing sets of values and laws. God’s Ten Commandments are the guardrails that guide and sustain all aspects of life, both private and collective, personal and institutional, ensuring justice, harmony, moral integrity, and unity.

To make this same point, William Barclay wrote:

“Without the manward look, religion can become a remote and detached mysticism in which a man is concerned with his own soul and his own vision of God and nothing more. Without the Godward look a society can become a place in which, as in a totalitarian state, men are looked on as things and not as persons. Reverence for God and respect for man can never be separated from each other.” [2]

Liberty and conflicts with democratic values

The first commandment, “You shall have no other gods before me” — the worship of God — is the epicenter from which liberty, inalienable (God-given) rights, equality under the law, democracy, and similar concepts flow. No other god or deities venerated or worshipped, so profoundly afford these principles.

For instance, excluding Christianity, the top three other religions in the world with the most followers would be Islam (1.9 billion), Hinduism (1.2 billion), and Buddhism (500 million). Each of these religions, in various ways, conflicts with core democratic values.

Islam and democratic principles

Islam is a monotheistic religion centered on the belief in one God (Allah) and the teachings of Muhammad. It adheres to Sharia, a comprehensive legal and moral code derived from the Quran and Hadith, governing diverse aspects of life, including religious practices, civil, criminal, and personal matters. Sharia conflicts with democratic principles in several ways. In nations such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, Sharia significantly influences the civil and criminal justice systems, including severe punishments for crimes such as theft (amputation) and adultery (stoning). Saudi Arabia has historically imposed strict limitations on women’s rights, including restrictions on driving, traveling without a male guardian, and participating in certain professions. Despite recent reforms, gender inequality remains significant. The country also enforces stringent laws against blasphemy and dissent, severely penalizing criticism of the government or religious authorities, thus limiting public discourse and suppressing political opposition. Similarly, Iran enforces strict blasphemy laws and suppresses political dissent, with journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens facing imprisonment, torture, or even execution for expressing critical views.

Hinduism and the caste system

The Hinduism of India, with its diverse pantheon of gods including Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, is deeply intertwined with the caste system. The caste system is a social hierarchy that categorizes people into four main castes: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras, with Dalits falling outside this structure and facing severe forms of discrimination. This system fundamentally contradicts the democratic ideal of equality by assigning social status, occupation, and even marriage prospects from birth, all of which can perpetrate social and economic disadvantages for those who are believed to have lived previous lives and are deemed only worthy of being in the lower castes. Although India has made some efforts to abolish caste-based discrimination, these disparities continue to persist in ways such as education, employment, and political representation. The ongoing practice of manual scavenging and caste-based violence highlights the conflict between Hinduism’s caste system and the superior ideals of everyone being endowed by their Maker with equal rights and opportunities in their pursuit of happiness.

Buddhism and national identity

Buddhism, which revolves around the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha), is a religion that promotes compassion and non-violence but still has been known to have negative implications when entangled with national pride. In countries such as Myanmar, Buddhism has been the platform for authoritarian regimes to justify oppressive policies and suppress democratization efforts. The persecution of the Rohingya Muslims, framed as a defense of national and religious identity, demonstrates how certain religious expressions can be used to undermine civil liberties and religious liberty. This historical and political muddling reveals the way the tenets of Buddhism when applied to national life, come into conflict with the people’s freedom.

The theistic foundation of nations

The late Dr. D. James Kennedy of Coral Ridge Ministries was noted for often saying in his books and sermons that it comes as a tremendous surprise for people today to learn that throughout history, every nation has been established on a foundation that is either theistic or anti-theistic. This includes ancient civilizations like Egypt, Babylonia, Syria, and Rome, as well as contemporary countries such as England, India, Russia, China, and the United States. Each nation is built upon either a religious or non-religious basis. From this foundational belief system, a corresponding set of ethics or morals emerges. These ethics or morals, in turn, shape and influence the legislation enacted within each nation. [3]

No, the first commandment, “You shall have no other gods before me,” should not be legislated. Because this commandment, as well as the three that follow it, is about how the One and only true God should be worshiped. True worship cannot be coerced, it must be voluntary.

Nevertheless, whatever god or gods people adore (polytheism, henotheism, theistic, non-theistic, atheism, materialism, secularism, humanism), to whatever they believe and give their allegiance, makes all the difference in the world. People become like the gods they esteem. Worship the right God and one gets the right results. Worship the wrong god or even a perversion of the real God, and it will end badly. What is true for the individual is true for the nations.

“You shall have no other gods before me.”

Resources:

[1] Taylor G. Bunch, The Ten Commandments: The Law of Liberty (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing, 1944), 23

[2] William Barclay, The Ten Commandments for Today (New York, Evanston, San Francisco, London: Harper & Row Publishers, 1973), 12

[3] D. James Kennedy, America Adrift (Fort Lauderdale: Coral Ridge Ministries, Speech Delivered to ‘Concerned Charlotteans” in Charlotte, N.C.) 1