Why Is Rachel Weeping in the Christmas Story?

When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi. Then what was said through the prophet Jeremiah was fulfilled:

"A voice is heard in Ramah,

weeping and great mourning,

Rachel weeping for her children

and refusing to be comforted,

because they are no more" (Matt. 2:16-18).

This Christmas you will almost certainly not hear a sermon preached on the passage above, but you should.

The problem is that we don't see the Old Testament in its full redemptive, historical context. This is why, at IFWE, we talk so much about the importance of seeing the whole redemptive metanarrative of the Bible being told as one story, in four chapters: creation, fall, redemption, and restoration.

The Bigger Story Surrounding Herod's Tragic Decree

Matthew's original audience consisted of Jews in the first century. The first two chapters of the book of Matthew (the story of Jesus' birth) illustrate how Matthew perceives Christ in the Old Testament in a larger historical, redemptive context.

In the first verse of "O Come, O Come, Emmanuel," the unknown 12th– century Latin hymn writer captures the essence of the theme that Matthew is seeking to introduce in the first two chapters in his gospel—a theme that will echo throughout the book.

O come, O come Emmanuel, and ransom captive Israel,

That mourns in lonely exile here, until the Son of God appears.

Matthew wanted his Jewish readers to understand that God's people were still in exile. Even though a remnant returned from Babylon and lived in the land, God's people still lived not only in spiritual exile but remained under the physical bondage of sin and death.

The Old Testament prophecy of restoration by Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the other prophets was, as yet, unfulfilled. The most telling sign of this continued exile was the absence of the "glory of the Lord" in the second temple. Ezekiel witnessed the departure of the "glory of the Lord" from the first temple (Ezek. 10) and it did not return with the building of a new temple after the Babylonian exile. Rachel wept and could not be comforted because her children remained in exile.

Israel Still in Exile

We see Matthew establishing the motif of continued exile from a number of different places in the first two chapters of his gospel account.

In Matthew 1:21, Joseph is told regarding Mary, "She will give birth to a Son, and you are to give Him the name Jesus, because He will save His people from their sins." God's people were still in bondage, enslaved by sin and in need of a deliverer.

In Matthew 2:6, we see this Messiah described as a "ruler, who will shepherd my people Israel"—One who will lead them out of exile, like a shepherd leads His sheep to safety. In verse 14, we see the holy family fleeing to Egypt for safety, fulfilling "what the Lord had said through the prophet: 'Out of Egypt I called my son'" (Matt. 2:15).

Things were so bad in Israel that Herod and those in power were now seen as "Egypt" in the eyes of Matthew. He reinforced this idea in Matthew 2:16 by describing the slaughter of the innocents, an event in which King Herod of Israel acted like the pharaoh of Egypt in the days of Moses.

Matthew looks back into the redemptive history of God's people and reminds them of another time when they were in exile: a time when God raised up Moses who successfully delivered the people out of bondage. As successful as this first exodus was, it was not the definitive escape because God's people fell back into exile.

The Ultimate Deliverer

In the second chapter of his gospel, Matthew draws strong parallels between Moses and Jesus to show that Christ is the fulfillment of the successful deliverer typologically signified by Moses.

Yet, this better Moses will lead "God's people" out of exile into the fulfillment of all that has been promised by the prophets. And as Moses successfully led Israel out of Egypt to the promised land, Christ will lead the final exodus, which will deliver all God's people from the exile of sin and death into the ultimate promised land.

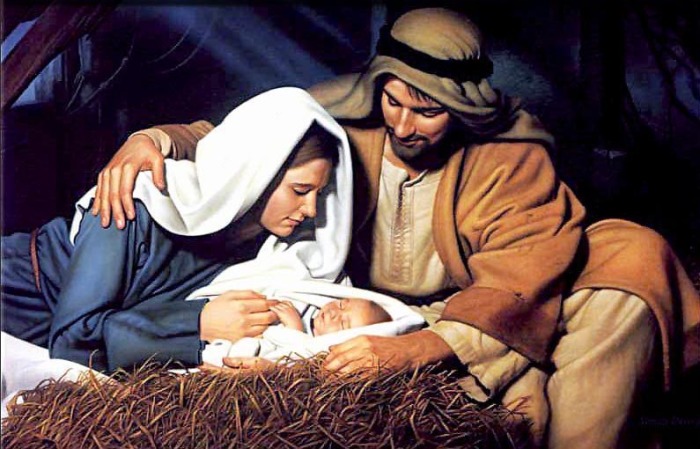

Matthew is telling them and us that the final exodus has begun with the birth of the Son of God, in a manger in Bethlehem. That better Moses, Jesus Christ, came, in part, to see that Rachel and all those who weep would finally be comforted.

The reference to Jeremiah 31:15 in Matthew 2:18 would have reminded Matthew's Jewish audience of the promises of the new covenant and of the promised Messiah who would make them a reality.

No More Weeping

Understanding the larger context of God's redemptive story helps us understand how our story plugs into his story. Through Christ's birth, life, death and resurrection, those of us who are in him, like the Israelites enslaved in Egypt, have been set free.

Yet, like the Israelites who crossed the Red Sea on dry land, we have not yet stepped into the promised land. We live and work in the third chapter of the four-chapter gospel—redemption—where we truly have tasted the way things could be. But we await the second coming of Christ and the final chapter of restoration, to live in a new heaven and a new earth with him forever.

When we fully enter into that glory at His second coming and stand in the new heaven and the new earth, "He will wipe every tear from [our] eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away" (Rev. 21:4).

On that glorious day, Rachel and all those who weep will finally be comforted.

This is what Christmas is really all about.

Originally posted at The Institute for Faith, Work & Economics (IFWE).