Criticism of slave memorial at Southern Seminary illustrates complexities surrounding issues of racial reconciliation

A commemorative plaque placed in the lobby of the Broadus Chapel at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary that President Al Mohler says is meant to serve as a “prominent” acknowledgment of the contributions enslaved people made in building the Louisville, Kentucky, institution is being challenged as a disappointing celebration by two outspoken black Southern Baptist ministers.

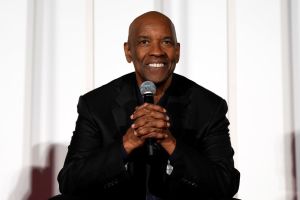

The controversy over the memorial erupted after Pastor Dwight McKissic, who founded and leads Cornerstone Baptist Church in Arlington, Texas, visited the seminary in June and noted that he did not “see a memorial erected to the slaves who built SBTS” that Mohler promised in 2020.

“I did see buildings & memorabilia honoring the four racist/sexist founders. However, I didn’t see any memorial erected honoring the slaves who funded & physically constructed the original campus,” McKissic remarked in a post on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, after his visit.

“As [I] walked on old cobblestone bricks at one point, I couldn’t help but wonder had slaves actually handled those bricks. President Mohler promised to build a memorial honoring the slaves, and I trust he’ll keep his word before he retires,” McKissic continued. “I promised to give toward helping toward that end, within my very limited financial capacity. I will keep my end of my commitment, by contributing a modest gift towards that project if he keeps his.”

In 2020, McKissic called for the renaming of Boyce College, the private college located at SBTS, amid a general outcry from racial justice activists across the country for the removal of statues of slaveholders from public spaces as well as their names from buildings in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, which rocked the nation that year.

Prior to that call, Mohler had urged the SBTS community in 2018 to repent of the sin of racism in a 71-page document called, “Report on Slavery and Racism in the History of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.”

“We must repent of our own sins; we cannot repent for the dead. We must, however, offer full lament for a legacy we inherit, and a story that is now ours,” Mohler wrote to the school founded in 1859 as part of the pro-slavery SBC.

It was noted in the report that James P. Boyce, the founder, and first president of the SBTS and other founding faculty — John A. Broadus, Basil Manly Jr. and William Williams — all owned slaves. Together, they owned more than 50 persons and invested capital in slaves who could earn for their owners an annual cash return. The seminary’s early faculty and trustees also defended the righteousness of slaveholding.

Despite calling for repentance for “a legacy [of slavery] we inherit, and a story that is now ours], Mohler, who previously noted in June 2015 that he had no intention to remove the names of any of the founders from the school’s buildings, reiterated that commitment in 2020 in response to McKissic’s call. He offered, however, to erect a memorial to the enslaved people who were held by the seminary’s founders.

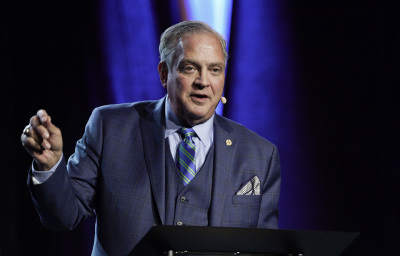

On seeing McKissic’s post on X in June, Mohler replied with an apology and noted that the memorial was already done and “is quite prominent” on the school’s campus. The SBTS president further offered to show the Texas pastor where the memorial is located if he would rejoin him on the campus to have a look.

“Pastor, glad you visited. Sorry you did not see the memorial. It is quite prominent. You had suggested it, and we followed up as promised. Your suggestion was right and timely. If you have time to come back, I will gladly show it to you this afternoon,” Mohler wrote.

McKissic was unable to return to the campus but Deryk Hayes, pastor of Saint Paul Baptist Church at Shively Heights in Louisville, replied in a post on X with a photo of the memorial.

“I’m no scholar but prominent seems to be somewhat of a stretch in my estimation. Again, I’m no scholar. Neither am I [a] dummy … the very placement of this plaque proves at the very least that @albertmohler is either culturally insensitive or ignorant. The founders aren’t heroic!” Hayes wrote.

Hayes, who would later reveal to The Christian Post that he is also one of a few black students enrolled at the seminary, was not pleased with the inscription on the plaque nor the placement of the plaque on a building that celebrates one of the founding faculty members.

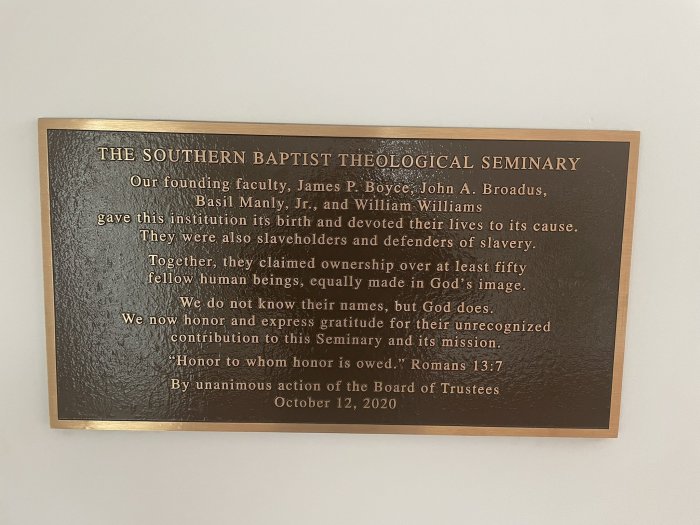

“Our founding faculty, James P. Boyce, John A. Broadus, Basil Manly Jr., and William Williams gave this institution its birth and devoted their lives to its cause,” the inscription on the memorial began.

“They are also slaveholders and defenders of slavery. Together they claimed ownership over at least 50 fellow human beings, equally made in God’s image,” the inscription endorsed by the unanimous action of the seminary’s Board of Trustees on Oct. 12, 2020, added. “We do not know their names, but God does. We now honor and express gratitude for their unrecognized contribution to this seminary and its mission. ‘Honor to whom honor is owed.’ Romans 13:7.’”

In a statement shared with CP on the memorial, McKissic said he harbored greater expectations of what the slavery memorial at SBTS would have looked like compared with the photo of the plaque shared by Hayes.

“I must admit that I was hopeful and searched for a memorial so prominent and visible that I could not have missed it. In my mind, I pictured an outdoor, highly visible memorial that could not be overlooked. No one told me that. It was simply what I had hoped for,” he said.

Even though he promised to donate to the erection of the memorial honoring the enslaved men and women who helped build the seminary, no one informed him that the plaque had been made and placed in the Broadus Chapel for viewing.

McKissic said he only decided to check the campus of the seminary for signs of the memorial after reading a tweet from fellow Southern Baptist Pastor Alan Cross referencing the school’s history of slavery.

“It triggered my memory to go and see if a memorial was actually there. I made a quick, hurried visit to a couple of buildings on campus, [but] did not see it. And I looked outside on the lawn and still did not see it. I assumed one had not been erected. But if I can be honest, I fulfilled my commitment to make a donation by sending Southern Seminary a $2,000 donation which was my estimate that should at least cover the cost to erect the plaque,” he said. “A more expansive and expensive memorial would have required a larger donation. So, the size of the memorial saved me money.”

When asked about the memorial, its formal announcement and placement on the campus of the seminary on Wednesday, Mohler told The Christian Post in an interview that the memorial was placed in Broadus Chapel shortly after the promise was made to add it to the campus in 2020. He said they also consulted with several black students and a black member of the seminary's board of trustees to decide on a fitting tribute.

"I consulted with some African American students, and we have an African American board member who was involved in this decision," Mohler told CP, noting that they also felt the Broadus chapel was the best place to show off the marker.

"We intentionally put the marker in a very strategic place which is in the main entrance to one of the most historic spots, prominent spots on the campus, which is in the foyer of the Broadus Chapel," Mohler explained. "I guess there are persons who could say it could be in a more prominent spot, but, frankly, I'd be hard pressed to find an area of wall on which a marker could be made that would be more prominent."

He noted that the SBTS board of trustees also had a restricted celebration of the marker at the time it was unveiled due to COVID-19.

"We invited a lot of people from the campus (to be a part of it), but let me remind you, we were doing it under the situation of COVID when we could not have large assemblies," Mohler said. "It was not in time for a public ceremony. It wasn't possible."

Mohler noted that even though some people may criticize the marker as insufficient, he is also aware that everyone would not be pleased with what they have done to celebrate the slaves.

"We put up that marker in good faith. We stand behind it. It is a public statement. I realize that does not please everyone as sufficient for what they would hope," he told CP. "I can say on behalf of the institution, we want to do everything that is right. But clearly, there's a level of disagreement about what that right action would be."

McKissic said even though he is disappointed by the stature of the memorial on the SBTS campus, he is “grateful that Dr. Mohler kept his word by acknowledging the role of the enslaved and their financial and labor contribution dedicated to the formation and founding of Southern Seminary.”

Though he celebrates the acknowledgment of the contributions of slaves to SBTS, McKissic made it clear that it doesn’t make up for the seminary leadership’s refusal to scrub the names of the slaveholding founders from the school’s buildings.

“I still think the names of the slaveholding founders should be removed from the buildings on campus,” he said, but he does not believe Mohler and the leadership team “have the inner, moral wherewithal” to do it.

“They obviously value the slave masters more than they did the enslaved, and they are not willing to admit the magnitude in which they were wrong and to deny the fruit of repentance by removing the names of these slave masters,” McKissic added.

Hayes argued that if visitors were to intentionally go searching for the SBTS slave memorial on a random visit, it would be difficult to find on the campus because there is no guide directing them to the plaque.

“You know, I walked around the campus looking for it. I asked the employees, have they seen it? The way I was able to find it is I asked the campus police,” Hayes told CP. “The campus police called two or three staff members, and one of the staff members was able to tell the campus police exactly where it was at. The campus police told me where it was located, and I went and looked at it and took the picture.”

Hayes said he found both the quality and placement of the memorial to the enslaved at SBTS disingenuous.

“I'm certain that a number of the faculty and staff were not aware of that plaque or what that plaque said. And I don't know how much noise has been made about the plaque. ... [The] truth is, there's nothing significant about the plaque. There's nothing prominent about where the plaque is placed, the plaque itself or what's written on the plaque,” Hayes said, likening it to a mere "footnote."

“I think that's a perfect way to explain it. It's a footnote. And I believe that it's also Al Mohler telling black people who speak out about it, I think it's Al Mohler's way of saying hush.”

The National African American Fellowship, a network of more than 4,000 predominantly African American churches affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention, boasts more than 400,000 members (slightly less than half of the over 880,000 black church members at Southern Baptist churches) but constitutes just over 3% of the denomination's 13.2 million-strong community.

The Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission reports that, in 2020, the number of African American church members at Southern Baptist churches was 880,108. According to BaptistResearch.com, in 2021, that number grew to 885,520 African American Southern Baptists, which accounts for 6.47% of the denomination's membership.

Data show that of the 4,448 students enrolled at SBTS, only 128 or approximately 3%, are recorded as black or African American.

Since 2018, the seminary has designated scholarships for black students as part of the Garland Offutt Scholars Program named in honor of the seminary’s first African American graduate. The seminary states that the scholarship "is designed to redress the legacy of slavery and legal segregation in the United States ..."

While there have been efforts made by the SBC to better address issues of race and racism over the years — including the historic SBC Resolution on Racial Reconciliation in 1995, in which the convention officially apologized for the denomination having supported slavery and segregation, and asked forgiveness from their African American brothers and sisters — the SBC has struggled to engage black adherents on issues like racial reconciliation and critical race theory to better understand how racism impacts the community. A dispute over CRT in 2020 led a number of black churches to cut ties with the denomination.

Hayes argues that Mohler’s treatment of the memorial shows that he lacks cultural competence and that “he has to be discipled in that area.”

“He's not only insensitive but he doesn't have the capacity to even want to understand systemic oppression," Hayes said.

The Louisville pastor, whose church is loosely affiliated with the SBC, said he led a predominantly white congregation before moving to his latest congregation, which was created from a merger between a predominantly black church and a predominantly white church in 2009.

He admits that when he first started attending SBTS as a graduate-level student, he quit because he became uncomfortable. But God called him back.

“Initially, to be honest with you, when I first started, I withdrew [for a while] because I just didn't want to be a part of that climate and that content. I was so uncomfortable,” he explained.

He said he went back because, “I am convinced that this is a part of the call that God has on my life.”

“I felt compelled, and to be honest with you, having to repent because ultimately I felt like I disobeyed God,” Hayes said.

“There are people right now that know that I go to Southern, and you know, in their eyes, I'm a sellout. I'm an Uncle Tom and a number of things that they call me. But the truth is, I believe that I'm operating according to God's will for my life. And I believe if I'm obedient to God, then I can make a difference in the space that God has called me to.”

Unlike McKissic, Hayes does not celebrate the plaque as a small win.

“For me, it's not it's not enough. I would rather they didn't put a plaque up at all than to put what they put up and put the plaque where they put it. I would rather the library that has been redone and it's partially open right now, particularly for students, to be named for the first African American graduate of the Southern Baptist seminary, Dr. [Garland] Offutt, rather than it being the Boyce library or whatever the library is called,” he said. “That would be something prominent.”

“It would be more prominent if you had a plaque for those who were enslaved, it would be better to put it out into the open somewhere to give it a significant size to somehow make it attractive,” Hayes explained.

“If we really want to do some of the things that I believe Al Mohler said that he wanted to do as far as reaching, particularly African American people, and doing right by African American people, I think at the very least, that's some of the things that Dr. Mohler should do,” he said, noting that he would also love to see the hiring of more African American professors.

He said the treatment of the slave memorial made him question Mohler’s sincerity.

“I think, first of all, we got to ask, What's the motive behind that? Is it to silence Pastor McKissick? Is it for Pastor McKissick and other black pastors to say this is good enough?” he asked.

“A better way to apologize and repent of systemic racism is to take the names of slaveholders [off] school buildings,” Hayes said. “When I go in certain buildings, I don't want to see pictures of men being portrayed as heroes who enslaved people that look like me.”

Contact: leonardo.blair@christianpost.com Follow Leonardo Blair on Twitter: @leoblair Follow Leonardo Blair on Facebook: LeoBlairChristianPost