Andrew Brunson considered suicide in Turkish prison as he felt betrayed by God

Spending 735 days detained in Turkey before being released last year thanks to United States diplomatic pressure, North Carolina missionary Andrew Brunson became somewhat of a hero in the eyes of many American evangelicals for standing strong in his faith despite the persecution.

However, the 51-year-old Brunson admits in a new book to be released Tuesday that there were times throughout the ordeal that he questioned whether God picked the right man for the “assignment” and even contemplated the idea of taking his own life.

Having spent months in one overcrowded cell with Muslim cellmates, Brunson has opened up about how he toed the line of insanity and felt at points that without access to his family or the Bible that God turned him over to Satan.

At one of his lowest points in prison — the day after Christmas 2016 — Brunson admitted that he tested the clothesline of the prison courtyard to see if it could hold his weight. In his distraught mind, he began to believe that ending his life would be better than falling away in his faith.

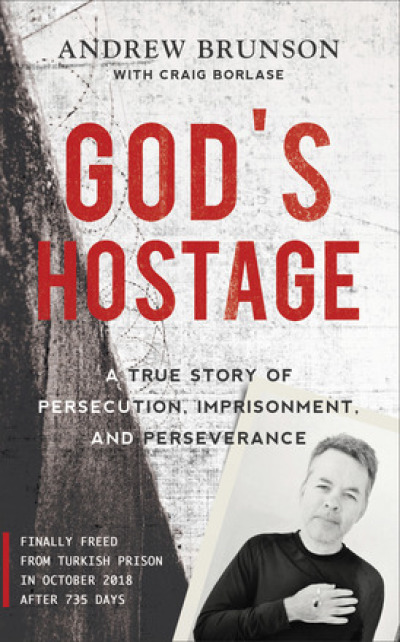

“It gave me a sense of comfort to know that I could escape this nightmare,” Brunson wrote in his new book, God’s Hostage: A True Story of Persecution, Imprisonment, and Perseverance. “And knowing this lifted my despair just enough to help me hold on.”

Brunson spent 23 years as a missionary in Turkey before he was arrested in October 2016 along with his wife, Norine.

The Brunsons were arrested at a time in which the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was arresting and imprisoning thousands of people accused of being involved in the coup attempt of July 2016 or being supporters of Islamic cleric Fethullah Gulen.

Although Norine Brunson was released after 13 days, Andrew Brunson was not. He was sent to solitary confinement for about 50 days at a deportation detention center and was later sent to a high-security prison for 8½ months where he had to share a cell designed for eight people with over 20 other men at points.

It wasn’t until about 18 months after Brunson was imprisoned that he was formally charged with terrorism and accused of having connections to Kurdish militants and a group blamed for the coup attempt against the Turkish government.

Brunson has continually denied the charges and international rights advocates accused Turkey of holding Brunson hostage in an attempt to get the U.S. to extradite Fethullah Gulen, an Islamic cleric whom the Turkish government accused of being the mastermind behind the coup attempt.

Although Brunson was an innocent man, doubts crept in his mind early on about whether or not he would ever get out of prison.

In a chapter titled “Meltdown,” Brunson and co-author Craig Borlase detail the emotional and spiritual struggle that Brunson faced when he was imprisoned in an overloaded cell at Sakran high-security prison.

In Sakran, there were no communal spaces or daily activities for inmates. For the most part, inmates are forced to stay in their cells without much to entertain themselves.

On Mondays, prisoners in Brunson’s cell were allowed to have family visits. On that first Monday that Brunson was at the prison, he was excited at the chance to see Norine and his lawyer. However, he was the only one from his cell who was not allowed to have visitors that day.

Brunson, not having seen his wife for weeks at that point, went out into the prison courtyard where he paced and looked up to the sky. Seeing the high walls surround him, he felt as though he was in the “bottom of a pit.”

At that point, he voiced his frustration with God.

“You’ve betrayed me! You’ve turned me over! Why?! How could You do this to a son who loves You, a son who has obeyed You?” Brunson recalled questioning the Lord. “Do You even care, or have You handed me over and walked away? Did You deceive me? Did You lie to me?”

For Brunson, being thrown in prison was an “unexpected change” because it hadn’t happened to any missionaries in Turkey and he had never prepared himself for such a possibility.

He couldn’t cope with the “horde of questions” that were plaguing his mind. Additionally, there was no one he could turn to.

He couldn't turn to his cellmates and he was being prevented from speaking to his closest confidant in the world, his wife. Brunson said that he couldn’t even turn to God at that time.

“He had turned me over to be savaged,” he wrote, adding that the only thing he was hearing from God was “silence.”

While he had heard many stories of Christians imprisoned by the government in China who were joyful for the proximity to the Lord they felt during their imprisonments, Brunson said that he did not experience that type of proximity to God when he was locked away.

“How could I be so broken by prison? What was wrong with me? I said time and again, ‘God, you chose the wrong man,’” Brunson wrote. ‘Why would He put me in a place where I would start to believe that it’s harder to live for God than it is to die for Him.”

On the day after Christmas in 2016, an open visit was held at Sakran prison. Although families were allowed to visit with inmates, Brunson was not granted this luxury. At this point, he had gone three weeks without seeing his wife and was growing “increasingly desperate.’

“Even more terrifying was the fear that I might lose my faith. I had no desire to reject my faith — actually, I was desperately clinging to it,” the book reads. “But I was afraid that with all my questions, doubts and isolation from anyone who could encourage and correct me, I would in some way fail and turn away. The words of Jesus came to mind — that if your hand causes you to sin, then it's better to cut off the hand and go to Heaven than to keep both but go to Hell.”

He wondered if it would be “better to kill myself to ensure that I didn’t lose my faith.”

“In my twisted thinking, it made sense,” he continued. “When the men filed out to meet their families on December 26, I was the only one left behind in the cell. I went out to the courtyard. I tested the rope. Yes, the clothesline was strong enough to hold my weight. I was ready to go to Heaven.”

Follow Samuel Smith on Twitter: @IamSamSmith

or Facebook: SamuelSmithCP