Biden signs law making lynching a federal hate crime after century of failed attempts

President Joe Biden has signed a bill into law that makes lynching a federal hate crime after generations of failed attempts to do the same.

The bipartisan House Resolution 55, also known as the Emmett Till Antilynching Law, was signed on Tuesday at a ceremony held in the White House Rose Garden, making lynching a hate crime that carries a punishment of up to 30 years in prison and a possible fine.

Till was an African American teenage boy brutally murdered in 1955 by two men after a white woman claimed that he had whistled at her.

“Till was born nearly 40 years ago after the first antilynching law was introduced. Although he was one of thousands who were lynched, his mother’s courage to show the world what was done to him energized the Civil Rights Movement,” said Biden.

“To the Till family: We remain in awe of your courage to find purpose through your pain. But the law is not just about the past. It’s about the present and our future as well.”

Biden claimed that racism is “a persistent problem,” adding that “the same racial hatred that drove the mob to hang a noose brought that mob carrying torches out of the fields of Charlottesville just a few years go.”

“Over the years, several federal hate crime laws were enacted, including one I signed last year to combat COVID-19 hate crimes. But no federal law — no federal law expressly prohibited lynching. None. Until today,” he continued.

The new law was passed by the House of Representatives in February by a vote of 422 yeas, three nays and eight members “not voting.”

The bill was passed in the Senate unanimously earlier this month.

Rep. Andrew Clyde of Georgia, one of three Republican congressmen to vote against the measure, argued that the federal anti-lynching law is unnecessary in light of pre-existing laws.

“Lynching is an evil act of violence that is already against the law at the federal level; it is first-degree murder,” Clyde said in a statement, as quoted by The Gainesville Times.

“Furthermore, my home state of Georgia recently signed hate crime legislation into law this past year. H.R. 55 would create no new federal offense and the current hate crime criminal code already establishes penalties for willful bodily injury to another person.”

Clyde further argued that “we do not need another duplicative federal law.” He claimed the new law “falsely suggests that individuals who commit, or attempt to commit, a lynching do not already face criminal charges and consequences.”

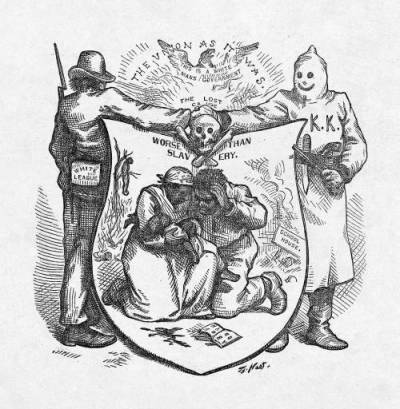

From the end of the American Civil War well into the 20th century, lynching was often committed by white mobs in both northern and southern states to attack African Americans.

It was not uncommon for communities to treat lynchings as social events. Many whites infamously took photos of themselves alongside mutilated black corpses and sent them to friends and family.

Efforts to enact federal measures against lynching go as far back as at least the year 1900, when Rep. George Henry White, R-N.C., the only African American in Congress during that time, introduced H.R. 6963.

White’s proposed legislation failed to make it out of the House Judiciary Committee.

During the 1930s, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt passionately campaigned for federal anti-lynching legislation. However, Southern Democrats in Congress helped defeat such proposals.

“There are mental and spiritual lynchings as well as physical ones, and few of us in this nation can claim immunity from responsibility for some of the frustrations and injustices which face not only our colored people, but other groups,” she later wrote in 1945.

In 2005, the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly passed a bipartisan resolution in which they officially apologized for failing to enact federal anti-lynching laws decades earlier.