Can Darwinian Evolution Explain Why Christians Help Others?

Do human beings do nice things because they're afraid that God will punish them if they don't?

One of the biggest stumbling blocks to a purely Darwinian explanation of the world is the persistence of traits and behaviors that, strictly speaking, don't further the purposes of what Richard Dawkins famously called "the selfish gene."

The most obvious stumbling blocks are human altruism and cooperation. If natural selection is a "zero sum game," that is, if your selfish gene wins, then my selfish gene loses, why should I bother to cooperate with you?

Attempts to get around this problem have amounted to little more than "just so stories": "unverifiable and unfalsifiable narrative explanations," often involving saber-tooth cats.

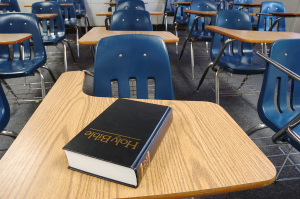

Here's the latest case in point: a solution that invokes, of all things, belief in God, or at least a god.

A paper recently published in the journal Nature concludes that the behaviors such as treating other people with fairness and impartiality made possible the creation of "large-scale cooperative institutions, such as trade and markets." The paper then goes on to say that these less-selfish behaviors were the result of "the fear that a punitive God is watching."

This religiously driven "magnanimous behavior . . . [may have been] what helped foster the trust needed for humanity's growth."

But how do we know whether this is, in fact, the case? After all, the people who were around during the creation of "large-scale cooperative institutions, such as trade and markets" aren't around to be interviewed.

The authors' answer lies in, of all things, the results of a series of games.

They gathered 600 people from around the world representing different faiths — including Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, animism, and ancestor worship — with "widely varying attitudes to divine retribution." They asked the participants to play a game "where they could offer a limited number of real coins to their own community, or to a group of fellow believers in a distant place who they had never met."

"The game was carefully designed to allow each participant to follow their own conscience in deciding which cup to put their coins."

They found that, "When people report not knowing if a god punishes, they put considerably fewer coins in the cups of distant co-religionists." From this they hypothesize that belief in a punitive god gave rise to treating people with fairness and impartiality.

They hastened to add that we should not draw "too strong a conclusion about the kindness of people of faith."

Of course not.

One obvious problem is that none of our very distant ancestors were Christians, Hindus, or Buddhists — these faiths arose long after the rise of agriculture and civilization. So what a modern Christian or Buddhist has to teach us about prehistoric people is very limited.

What the experiment actually shows is that some beliefs held by people today influence how they treat other people, which is, well, obvious. Furthermore, what's being described is not altruism or even generosity. It isn't even trust. It doesn't explain the actions of a Mother Theresa or the missionary doctors who ministered to Ebola patients during the recent outbreak.

In the biblical tradition, to say we "fear" God — the Hebrew word yare — means that we revere Him. Part of this reverence includes treating other people with kindness and generosity. Furthermore, as beings created in the image of a kind, generous, and magnanimous God, we are capable of these qualities.

It is this, and not primal fear bordering on superstition, that accounts for what Lincoln called the "better angels of our nature."

Originally posted at breakpoint.org