Investing your values: the real Game of Thrones

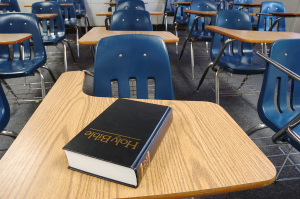

Solomon once observed, “The rich rule over the poor.” (Proverbs 22:7a) And since the advent of the first stock companies over 400 years ago, the world has never seen such an efficient economic invention with the power to rule.

Almost overnight, the East India Company and Dutch East India Company dominated global trading, and became powerful enough to overthrow the governments of China and India, the two most populous countries in the world. The wealth that was once in the hands of Kings and Queens, Emperors and Czars, is now in the hands of corporations. This shift in power effectively puts ruling into the hands of a much broader swath of humanity: shareholders and their boards.

The real Game of Thrones for the past four centuries is powered by our investments, and Christians neither can nor should abdicate our God-given responsibility to rule over His creation with the wealth He has entrusted to us in a way that glorifies Him. The brilliance of the corporate form as an economic instrument of prosperity, however, is dimmed by its void of any ethic outside that of maximizing the wealth of the firm.

Can we honestly pray that God’s ”will be done,” and His “kingdom come, on earth as it is in heaven,” and then complacently sit by with our wealth invested in a corporation where our sole purpose is to earn the highest possible rate of return?

Even the non-Christian world thinks this is a bad idea. And a growing percentage of investors are demanding more accountability for corporations’ actions. As they unite to voice their values, will Christian investors remain silent? Or will we draw a line in the sand and unite around clear Biblical principles to seek first God’s kingdom, and His righteousness?

It has taken the recent rise in socially responsible investing—alternately articulated as the Triple Bottom Line (that is, profit, people, planet), and ESG (that is, environment, social, governance)—to awaken Christians to the realization that there is an ethical component to our investments. Suddenly we are enraged that someone would have the audacity to vote their values, where we’ve failed to vote ours.

Christians have been content to allow the battle for the corporate soul to play out in the halls of academia, between the opposing views broadly labeled Stockholder and Stakeholder Theories. Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman’s Stockholder Theory argues that the corporation’s sole duty is to its stockholders, to maximize profits, and this quest should be limited only by the law and social norms. Any use of stockholders’ wealth beyond this goal is akin to taxation without representation. Stakeholder Theory opposes this viewpoint, arguing that there are many stakeholders in the corporation beyond the stockholders—from employees, to the people and environment in communities where corporations do business—and all have valid claims that must be met by the corporation.

As an accounting academic and a member of the 7,000+ American Accounting Association (AAA) academic arm of accounting, and former Chair of the AAA’s Public Interest Section, I’ve had a front row seat to observe some of the brightest minds attempt to develop metrics to measure their values. And while their values didn’t always align with mine, I have been struck by the Christian community’s lack of interest in expressing our own values. As Christians, we take pride in knowing the true God—who delights in “kindness, justice and righteousness” (Jeremiah 9:24)—and walking in His ways. If my atheist, socialist, communist, or anarchist colleagues care about corporations’ impact on the world, how much more concerned should we as Christians be?

There are two clear Biblical principles that warn us to be wary of this ethical void. First, Jesus warns us that money is a bad master:

“No one can serve two masters. Either you will hate the one and love the other, or you will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and Money.” (Matthew 6:24)

Maximizing the wealth of the firm is not a sufficient ethic. The simplicity of the corporate form is that it allows an entity to raise capital for any endeavor, with virtually no restrictions on who can join in the venture. The only agreement among shareholders is the quest for profit. The success of a corporation is measured by the price of its shares. This leaves Money, not God, as master.

The second principle comes from Apostle Paul’s warning:

“Do not be yoked together with unbelievers. For what do righteousness and wickedness have in common? Or what fellowship can light have with darkness?” (2 Corinthians 6:14)

While Christians frequently quote this verse as a warning against marrying outside our faith, the scope of Paul’s instruction clearly extends to the breadth of our lives, including how we invest. And ultimately how we rule.

How, then, should we invest?

We begin by recognizing the Biblical purpose for wealth.

What is the best use of our wealth? Jesus tells us, “use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourselves, so that when it is gone, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.” (Luke 16:9) When we use our wealth to love others as God has loved us, and give Him the glory, we simultaneously fulfill the Great Commandments and the Great Commission. In so doing, we make disciples. Friends forever.

Next, we choose influence over ignorance.

I freely admit my default position has been ignorance. If you are like me, you have been content to work hard, live beneath your means, and invest as religiously as you give. A simple recipe for financial success built on the Protestant work ethic and a tidy little portfolio diversified across the S&P 500. But are we more likely to be kept up at night by the threat of a Bear Market than concerns that our investments might be used for evil instead of good? As Christian investors, shouldn’t we be more concerned about the latter?

By choosing influence, Christian investors have an incredible opportunity to advance the kingdom, and his righteousness, through: 1) investing, 2) divesting, and 3) advocacy.

First, invest in corporations that create products and provide services that accomplish good. “Biblically responsible investing” is a means to obtain a portfolio of investments that aligns with your values, whether health care, insurance, food, banking, services, or REITs. As Christians, we often rely on generosity and giving to the church to accomplish the good we hope to see in the world. But as important as this is, almost all of the goods and services in the world are produced by for-profits, not non-profits. From the food we’re eating, to the homes and offices where we now sit, to the devices we’re using to communicate—most of our work in the world is accomplished through corporations, driven by the “invisible hand of the market.”

Second, divest in companies that oppose your values. You can omit certain companies from your portfolio, or rely on faith-based portfolios like GuideStone Funds to assist you. As an accounting academic, I recognize trying to implement “sin screens” for your investments is an area fraught with measurement issues, but just because it is challenging is no excuse for complicity.

Finally, advocate for what is right. Vote your values. Jerry Bower’s recent interview with Justin Danhof of Strive Asset Management in The Christian Post is an example of an expert who attends shareholder meetings to steer companies towards Christian values. Likewise, you can engage in the proxy process, or join with like-minded believers who can champion your values for you. William Wilberforce’s 20 year quest to abolish the slave trade in 1807 is a powerful example of the great things Christians can accomplish when we advocate for what is right.

Jesus warned the lukewarm church in Laodicea about their complacency:

“You say I am rich; I have acquired wealth and do not need a thing.” But in the eyes of God, they were “wretched, pitiful, poor, blind and naked.” (Revelation 3:17)

How does God view the church in America? Certainly investing for God’s kingdom is worth the work.

“To him who overcomes, I will give the right to sit on my throne, just as I overcame and sat down with my Father on his throne.” (Revelation 3:21)

Will we invest our wealth to gain friends forever? Or we gain only wealth? When it comes to investing well, there is only one throne that matters.

John Thornton is the L.P. and Bobbi Leung Chair of Accounting Ethics at Azusa Pacific University, and author of Jesus’ Terrible Financial Advice: Flipping the Tables on Peace, Prosperity, and the Pursuit of Happiness.