Syria and the War on Christians: Should the U.S. Intervene?

In the last week of April, two Orthodox bishops in Syria were kidnapped by rebels near Aleppo. Ironically, these same bishops "had warned of the threat to religious tolerance and diversity from the two-year conflict in their country."

It's a potent reminder that while we may not be certain who the winners in the upheavals rocking Syria and the rest of the Middle East might be, we already know who the losers will be: Christians.

That's the sobering conclusion of a recent piece in the American Conservative written by Andrew Doran, a former official at UNESCO and the State Department. While the article is ostensibly about how the war in Iraq became a war on Iraqi Christians, the lessons we failed to learn in Iraq are every bit as applicable, if not more so, in Syria.

Much of the story Doran tells will be familiar to long-time BreakPoint listeners. The United States gave virtually no thought to the impact that invading and destabilizing Iraq would have on the country's Christians. Concern for their fate is why the Vatican urged the Bush administration not to proceed.

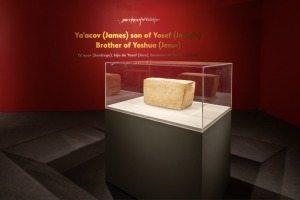

But the U.S. invaded, and the completely foreseeable happened: a Christian community whose roots can be traced to the Apostles themselves got caught in the middle. Virtually the only thing Sunni and Shia Muslims agreed on was targeting Iraqi Christians.

Ominously for Syrian Christians, the first targets in Iraq were the clergy. As Nina Shea and others, including Chuck Colson, pointed out at the time, the United States made no provision for protecting Iraqi Christians.

As a result, Iraqi Christians were forced to flee what one Assyrian Christian called an "incipient genocide." In the ten years since the invasion of Iraq, half of the country's Christians have left the country. Those remaining are still subject to attacks.

For those who left, the U.S. added insult to the injury of exile. Iraqi Christians seeking asylum in the USA were detained in what one activist calls "prisons;" and the vast majority were denied asylum even though if any group has a "well-founded fear of persecution" it's Iraqi Christians.

Ironically, the one place they have been able to find refuge is in the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq. In other words, Kurdish Muslims have been more solicitous of our Christian brethren's well-being than American Christians and their government.

Given this recent history, it would be willful folly, bordering on malice, to deny that the same thing can happen next door in Syria. As Doran wrote, "democracy in the Middle East is proving less tolerant than the regimes it has succeeded. Ask Egyptian Christians."

Then there's the increasing influence of Islamists, including al Qaeda affiliates, in the Syrian opposition. Doran is right when he writes that "the Islamist-Wahabbist commitment to eradicating Christian minorities today will result in the extinction of diverse modes of Islam tomorrow." While this fact is "not lost on moderate Muslims," it does seem to be lost on those urging the U.S. to intervene on the side of the rebels.

President Obama, concerned about what might come after the Syrian dictator Assad is ousted, is rightly hesitant about aiding the rebels. He doesn't want to create "another Iraq."

For that we should be grateful. The last thing we should want is yet another war on Christians in the land where believers were first called by that name.

But the pressure on the administration to intervene is growing. For the sake of our Christian brothers and sisters, let's pray that God will grant our leaders much wisdom before they act.