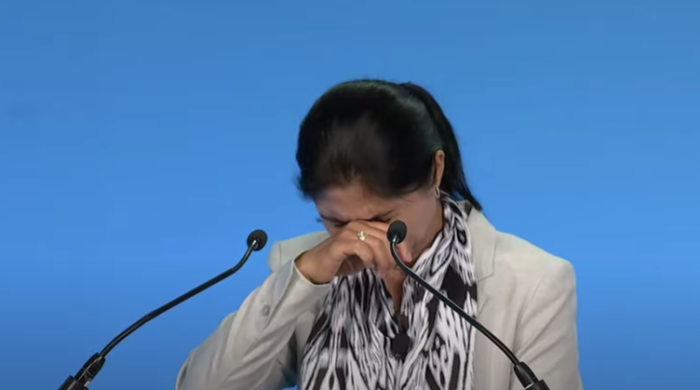

Uyghur woman tearfully recalls 'inhumane' treatment in China’s brutal concentration camps

WASHINGTON — A Uyghur tearfully recalled her time in a Chinese concentration camp in a speech before religious freedom advocates, telling them that her experience left “indelible scars on my heart.”

Tursunay Ziyawudun addressed the International Religious Freedom Summit on Wednesday, one of several survivors of religious persecution to share their stories. As a Uyghur living in China, she was subject to especially harsh treatment from the Chinese Communist Party, which is detaining members of the ethnic minority in concentration camps in an effort to strip them of their culture and identity and turn them into loyal servants of the state.

“I was locked up in camps two different times. The second time was even more inhumane than the first, and my experiences in these Chinese camps have left indelible scars on my heart,” she said.

“I was taken into a camp for the second time in March 2018 and stayed there for close to one year. There were many new buildings in the camp, which looked similar to a prison, and many cameras and people inside. We could always see armed police officers. Sometimes they showed us propaganda films, sometimes they taught us Chinese law, sometimes they taught us Chinese ‘red’ songs, and sometimes they made us swear oaths of loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party,” she added.

According to Ziyawudun, “In the camp, we always lived in fear. We passed the days in fear, listening to the sounds of screaming and crying voices, wondering whether what was happening to them would happen to us too.”

Ziyawudun and other detained Uyghur women were also subject to rape in the concentration camps, part of a pattern of abuse at the hands of the guards: “Once they took me out alongside a young woman in her 20s. Next to the camp police officers, there was a man in a suit, wearing a mask over his mouth. I can’t even remember what time of night it was. They raped the young women. Three Han police officers raped me as well.”

“They were always taking girls out of the cells like this. They did whatever they wanted. Sometimes they brought some of the women back near the point of death. Some of the women disappeared.”

Echoing comments she made in a previous interview with the BBC, Ziyawudun asserted that some of the women “lost their minds in the camp.” Additionally, she maintained, “I saw some of them bleed to death with my own eyes.”

As years have passed since her harrowing ordeal in the concentration camp, Ziyawudun explained that while “my physical body is free, and so is my voice,” she is “suffering deeply” as a result of “nightmares” about her detention. She has since resettled in the U.S., “with the help of the U.S. government and the Uyghur Human Rights Project.”

Although these memories make Ziyawudun’s heart feel “as though it’s been sliced with a dagger,” she feels obligated to tell her story: “I have to speak out, because the things that I experienced in the camps are happening to my fellow Uyghurs. Millions of Uyghurs are suffering and they are alive only because they have the hope and belief that there is justice in this world.”

“As a survivor, I will not stop — not even for one minute — being a voice for all the people who have not survived, and for the people in East Turkistan who are trapped in a hellscape, placing their hope in the outside world,” she vowed. Ziyawudun concluded her remarks by pleading with the audience to “save my people from this oppression,” adding, “I hope you can do something to secure their freedom.”

In an introductory video that preceded Ziyawudun’s remarks, a translator speaking on behalf of the victim of religious persecution illustrated the magnitude of the Chinese government’s “brutal campaign of assimilation by force,” noting that “1 [million] to 3 million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims” have been detained in concentration camps since 2016. In addition to rape, concentration camp detainees are subject to forced labor and forced sterilization.

Later, Samantha Power, the administrator for the U.S. Agency for International Development, told the story of another Uyghur woman who was subject to the concentration camps, Zumret Dawut, in pre-recorded remarks: “In 2018, she was told to report to a local police station before being interrogated, shackled with a black hood over her head, and led to a detention camp where she was forced to change into prison clothes in front of male guards.”

Power explained that Dawut, a mother of three who wanted to have a fourth child, ended up undergoing forced sterilization in lieu of facing additional detention. Even Uyghurs who have not been sent to concentration camps still face surveillance by the Chinese government.

During a panel on “Big Surveillance and the Rise of Technology in Persecution,” Uyghur-American lawyer Nury Turkel discussed the “digital authoritarianism” China has engaged in as part of its persecution of the Uyghurs: “Chinese officials, assisted by sophisticated technology, impose an iron grip over every aspect of life” by using “video cameras, equipped with facial recognition software.”

“Uyghurs must have their ID cards scanned at ubiquitous checkpoints to gain access to parks, banks, malls and stores. These scanners are linked to broader policing technology. If an individual is identified as risky, then entry will be denied,” he continued.

Turkel elaborated on the “broader policing technology” used on Uyghurs, including “QR codes posted outside of [a] Uyghur home to learn who lives there and how ‘trustworthy’ that they are,” as well as cell phones “equipped with mandatory spyware that records every aspect of Uyghurs’ online activity.” He stressed that the contents of Uyghurs’ private text messages have led some of them to face detention, lamenting that “Uyghurs cannot do anything to escape the watchful eye of the Chinese government.”

Ryan Foley is a reporter for The Christian Post. He can be reached at: ryan.foley@christianpost.com