World Food Program head warns of potential famines of 'biblical proportions' in 2021

The head of the World Food Program believes that 2021 could see “famines of biblical proportions” as the economic struggles of COVID-19 may hamper global responses to food shortages caused by military conflicts, the rise of Islamic extremism and locust infestations.

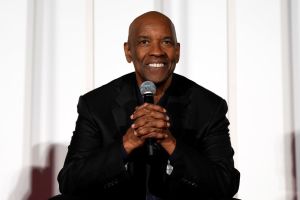

In an interview late last year with The Christian Post during a visit to Washington, D.C., WFP Executive Director David Beasley, a former Republican governor of South Carolina, expressed concern for the funding problems that could be in store for 2021.

Despite receiving historic levels of funding and leading the food-assistance branch of the United Nations to a Nobel Peace Prize since he took the helm in April 2017, the 63-year-old Beasley warned the fiscal realities of the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to a decrease in funding at a time when as many as 270 million could be pushed to the brink of starvation.

“When I joined the WFP, the number of people on the brink of starvation versus general hunger was 80 million people,” he explained. “There is a technical term for that. But it was 80 million marchings toward starvation. That number spiked, went up to 135 million at the end of [2019] primarily because of manmade conflict, compounded on top of that with climate extremes and destabilized or fragile governments. On top of that, COVID comes and the number we anticipated based upon economic deterioration and because of COVID decisions is now 270 million people that are marching to the brink of starvation.”

Last April as governments worldwide were enacting policies to respond to the pandemic, Beasley told the U.N. Security Council that funding shortfalls caused by the pandemic could cause “multiple famines of biblical proportions within a short few months.”

“I think it could be much bigger. It depends on how you define biblical proportions,” Beasley told CP. “In the generic sense, 2021 is going to be catastrophic unless we receive extraordinary financial support. I made a comment back in late 2019 that 2020 was going to be the worst humanitarian year since World War II. I would lay out the reasons why. Then before 2020 hit, desert locusts came on top of that, and then COVID came into the scene.”

“If we did not get the support we need and certain international actions were not taken, there would be famines of biblical proportions and destabilization and migration,” he added. “The international community responded very significantly in 2020. That has been very good and we have been able to avert famine this year.”

The director stressed that the problem for 2021 lies in the fact that government budgets for 2020 were largely set in 2019 based on strong economic indicators before the pandemic hit. WFP receives its funding in contributions from world governments as well as individual donations. In 2019, it assisted over 97 million people in 88 countries.

“With strong economic outlooks, great performance indicators, we had good budgeting,” he said. “That was good news. Then, COVID hits. The wealthy nations passed economic stimulus packages — between $11 and $17 trillion worth economic stimulus packages — to help jumpstart the economy and keep things going without having a major economic depression because of the lockdowns and shutdowns.”

Beasley said he was concerned by some of the decisions some governments were making in response to COVID.

“[L]eaders at that time were making decisions about COVID in a vacuum, not understanding the economic ripple effect when you just lock things down, without understanding the supply logistics and all these different dynamics,” he said.

“You cannot make decisions about COVID in a vacuum. We have to work it together and we can minimize death and destabilization and migration.”

In November, Beasley met with U.S. lawmakers, White House and State Department officials about the global situation, saying that “there is a lot of bad stuff out there right now.”

“In spite of what you might read in the press about the U.S. backing down of its multilateral commitment, as to the World Food Program, the United States is stepping up in a big way,” Beasley assured. “When you turn on the television and read any news, it appears that the Republicans and Democrats are fighting over anything and everything. But when I come to town and ask to meet, they lay down their differences and their guns and they make peace on this issue. I call it the miracle … because the Republicans and the Democrats come together.”

The former lawmaker said that Jesus used food as a “weapon of peace in a lot of different contexts.”

“We say we use food as a weapon of peace around the world and we have even used food in Washington,” he said. “If it works here, it will work everywhere.”

When Beasley took the job in 2017, the annual budget for the agency was about $5.9 billion, with just less than $2 billion coming from the U.S. According to Beasley, the WFP raised upwards of $8.4 billion in 2019, with about $3.5 billion coming from the U.S.

“I was also able to get funding up from Germany, the U.K. and others,” he said.

After assisting nearly 100 million people suffering from acute food insecurity and hunger in 2019, the WFP was the recipient of the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to combat hunger and generate better conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas.

According to The Norwegian Nobel Committee, the WFP acts “as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.”

Beasley recalled the day he was informed the WFP won the Nobel Prize.

“Very rarely am I speechless. That was one of the few moments,” he said. “I was in Niger that day. We had just been in the field out in a pretty rough area with extremist groups on all sides. We were working on access issues. When we don’t have access, they use food as a weapon of recruitment. Somebody comes busting in the door and says ‘We won!’ I was like, ‘You got to be kidding me.’”

As hunger is often used as a weapon of war, Beasley believes that “we can end hunger" if “we can end the wars."

Another major driver of hunger in 2020 has been a record infestation of crop-destroying desert locusts across several countries in East Africa and the Middle East.

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization warned last month that “new locust swarms are already forming and threatening to re-invade northern Kenya” while “breeding is also underway on both sides of the Red Sea, posing a new threat to Eritrea, Saudi Arabia, the Sudan, and Yemen.”

“We have done a lot of work and a lot of work to be done. There is a lot of distraction because of obvious things. We are making headway but we are not out of the woodwork yet,” Beasley said of the WFP’s locust response. “COVID has really [delayed] that progress. All the money we were going to put into desert locusts, you can imagine, everyone is fighting for every dollar now. But the locusts are not resolved and the locusts are moving.”

With millions on the brink of starvation, Beasley cited the “least of these” passage from Matthew 25 to state that “Jesus is making a clear point here.”

“Every human being is made in the image of God. Every human being is created in the image of the Almighty,” he said. “But when we deny that human support and love, then we are denying the Almighty. I look at everybody being equal and everybody is the same. Everybody on Earth has a right to [eat].”