Young people who leave church no longer returning as they get older, new research shows

While pastors have long banked on social science showing that young people who leave church generally return when they're older, a recent analysis of that trend suggests it might be over.

In his analysis of data from the General Social Survey of five-year windows in which individuals were born spanning from 1965 to 1984 and published by the Barna Group, Ryan Burge, an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and pastor of First Baptist Church of Mt. Vernon, Illinois, shows that younger generations raised in the church aren’t typically returning to church when compared with members of the “Baby boomer” generation born between 1945 and 1964.

In Burge’s analysis of the boomer generation, four different five-year cohorts reflected the “trademark hump” supported by traditional social science “when each birth cohort moves into the 36–45 age range. That’s exactly what the life cycle effect would predict: People settle down, they have kids, and they return to church.”

When he examined data for the younger cohorts 1965-1969, 1975-1979 and 1980-1984, the data show a fading of the life cycle effect. While the hump is still there in the cohort measured from 1965-1969, a shift in the life cycle effect begins to emerge by around 1970.

“That trend line is completely flat—those people didn’t return to church when they moved into their 30s. You can see the beginnings of a hump among those born between 1975 and 1979, but in the next birth cohort the hump is actually inverted. That trademark ‘return to church’—which pastors and church leaders have relied on for decades—might be fading,” Burge said.

For anyone concerned with church growth, Burge says “this should sound an alarm.”

“Many pastors are standing at the pulpit on Sunday morning and seeing fewer and fewer of their former youth group members returning to the pews when they move into their late-20s and early-30s. No church should assume that this crucial part of the population is going to return to active membership as their parents once did,” he explained.

“The data is speaking a clear message: the assumptions that undergirded church growth from two decades ago no longer apply. If churches are sitting back and just waiting for all their young people to flood back in as they move into their 30s, they are likely in for a rude awakening. Inaction now could be creating a church that does not have a strong future,” he added.

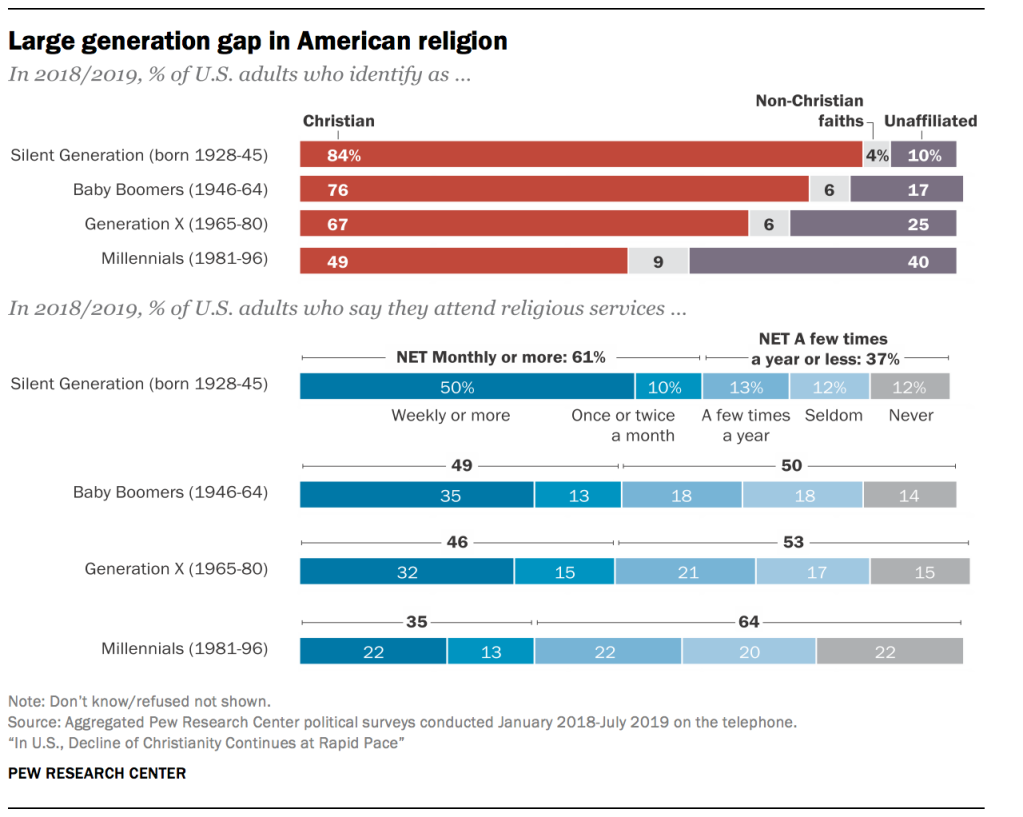

Just this month, a new study from the Pew Research Center noted that only 65 percent of Americans now identify as Christian while those who identify as religiously unaffiliated swelled to 26 percent of the population. The drop in the number of Americans identifying as Christian reflected a 12 percent decline when compared to the general population 10 years ago. The decline was visible across multiple demographics but particularly among young adults.

"Religious ‘nones’ are growing faster among Democrats than Republicans, though their ranks are swelling in both partisan coalitions,” Pew said. “And although the religiously unaffiliated are on the rise among younger people and most groups of older adults, their growth is most pronounced among young adults.”

Research by the Public Religion Research Institute in 2016 on why Americans are leaving religion previously pointed to the increasing share of American adults who have been joining the ranks of the religiously unaffiliated, and said it is being “fed by an exodus of those who grew up with a religious identity.” Younger Americans today are also more likely to be raised without a religious identity than seniors.

“Only 9 percent of Americans report being raised in a non-religious household. And while younger adults are more likely to report growing up without a religious identity than seniors (13% vs. 4%, respectively), the vast majority of unaffiliated Americans formerly identified with a particular religion,” PRRI said. “No religious group has benefited more from religious switching than the unaffiliated. Nearly one in five (19%) Americans switched from their childhood religious identity to become unaffiliated as adults, and relatively few (3%) Americans who were raised unaffiliated are joining a religious tradition. This dynamic has resulted in a dramatic net gain—16 percentage points—for the religiously unaffiliated.”

According to the 2016 PRRI study, nearly four in 10, 39 percent, of young adults ages 18-29 reported being religiously unaffiliated. This was three times the unaffiliated rate of 13 percent among seniors ages 65 and older.

“While previous generations were also more likely to be religiously unaffiliated in their 20s, young adults today are nearly four times as likely as young adults a generation ago to identify as religiously unaffiliated. In 1986, for example, only 10% of young adults claimed no religious affiliation,” the report said.

The PRRI research suggested that in the past it was the religiously unaffiliated who were more likely to join the affiliated in adulthood, but it is the now the inverse and the share of younger Americans being raised in nonreligious homes is growing.

“Not every religious community is equally successful in keeping members in the fold, and historically, Americans who were raised unaffiliated were among the most likely to switch their religious identity in adulthood. In the 1970s, only about one-third (34%) of Americans who were raised in religiously unaffiliated households were still unaffiliated as adults. By the 1990s, slightly more than half (53%) of Americans who were unaffiliated in childhood retained their religious identity in adulthood. Today, about two-thirds (66%) of Americans who report being raised outside a formal religious tradition remain unaffiliated as adults,” PRRI said.

“One important reason why the unaffiliated are experiencing rising retention rates is because younger Americans raised in nonreligious homes are less apt to join a religious tradition or denomination than young adults in previous eras. About three-quarters (74%) of Americans under the age of 50 who were raised nonreligious have maintained their lack of religious identity in adulthood. In contrast, only about half (49%) of Americans age 50 or older who were raised unaffiliated still identify that way,” the study said.

As younger Americans shift away from organized religion, the recent Pew study also suggests that Christians are declining not just as a share of the U.S. adult population, but also in absolute numbers.

“In 2009, there were approximately 233 million adults in the U.S., according to the census bureau. Pew Research Center’s RDD surveys conducted at the time indicated that 77% of them were Christian, which means that by this measure, there were approximately 178 million Christian adults in the U.S. in 2009. Taking the margin of error of the surveys into account, the number of adult Christians in the U.S. as of 2009 could have been as low as 176 million or as high as 181 million.

“Today, there are roughly 23 million more adults in the U.S. than there were in 2009 (256 million as of July 1, 2019, according to the Census Bureau). About two-thirds of them (65%) identify as Christians, according to 2018 and 2019 Pew Research Center RDD estimates. This means that there are now roughly 167 million Christian adults in the U.S. (with a lower bound of 164 million and an upper bound of 169 million, given the survey’s margin of error),” Pew explained.

The ranks of religiously unaffiliated adults in the U.S. meanwhile grew by almost 30 million over this period.

The PRRI study noted that a majority of Americans who left a religious tradition did not identify a particular negative experience or incident as their reason for leaving.

“In fact, more than two-thirds (68%) of unaffiliated Americans say their last time attending a religious service, not including a wedding or funeral service, was primarily positive. Only one in five (20%) unaffiliated Americans say their last visit to a religious congregation was mostly negative,” the study explained.

The study noted that another factor influencing the shift in more children being raised in religiously unaffiliated households is the increased likelihood of unaffiliated Americans marrying like-minded spouses.

“A majority (54%) of unaffiliated Americans who are married today report that their spouse shares the same religious background as they do. A generation earlier, unaffiliated Americans were much more likely to end up with religious spouses. In the 1970s, more than six in 10 (63%) unaffiliated Americans who were married reported that their spouse identified with a religious tradition,” PRRI said.

In his assessment of how churches can respond to the current falling away, Burge suggests churches can become more welcoming spaces for parents of infants and toddlers.

“I think one path forward is for churches to become intentional about providing welcoming and engaging spaces for parents of infants and toddlers. Things like free childcare during the worship service should be just the beginning. Events that allow exhausted parents the chance to talk to other people their age without having to watch their children like hawks would be a welcome relief. Churches should be encouraging groups like ‘Mothers of Preschoolers’ to meet in their spaces,” Burge said.

“If young people think that going to church is just going to consist of trying to keep their toddler from screaming the entire time, then staying home seems like a good option. And, if they find a church to be a welcoming space when their children are still toddlers, it stands to reason that they will be more likely to continue their attendance as their children grow older,” he added.